While John Rabe was living through one of the greatest acts of mass violence of World War II, his employers at Siemens China Company had no clue what he was doing.

The Japanese had censored communication to the outside world, and Rabe’s bosses were upset that he had not written. In January, the Siemens company sent him a terse note, scolding him for not leaving the city with the other Germans, and urging him to promptly exit and continue his sales work.

In February, as soon as the Japanese permitted foreigners to leave, Rabe followed his company’s orders. But when he left, he vowed to publicise the atrocities taking place.

Minnie Vautrin and other foreigners were sad to see him go, and Vautrin held a farewell tea party in his honour. After the tea, Rabe wrote of his deep admiration for Vautrin; “Miss Vautrin won my highest and very special respect in those worst December days when I saw her marching through the city at the head of 400 fleeing women and girls, bringing them to safety at the Ginling University camp”.

After the tea, at Vautrin’s Ginling College refugee camp, refugees surrounded the door, dropped to their knees and clung to Rabe’s coattails. They begged him not to leave. At that time, more than 2 months after Japanese had taken the city, rape and indiscriminate violence were ongoing.

Still, quietly, Rabe exited. He brought with him his diary entries, a film of the atrocities and a Chinese air force officer whom Rabe had been hiding in his house. Rabe pretended the officer was his servant, and successfully smuggled him onto a riverboat to Shanghai.

Rabe’s reception in Germany was mixed. As Iris Chang reported in her book, “The Rape of Nanking”, Rabe received awards from the Red Cross Order and the Chinese government. In May, he began lecturing across Berlin, playing the film he had smuggled out.

But his mistake came when he attempted to meet with Adolf Hitler.

Rabe believed Hitler would yield to a humanitarian impulse and perhaps pressure the Japanese to stop their gratuitous violence. At that time, the public did not entirely understand Hitler’s efforts to eliminate Jews.

Days after Rabe sent a letter to the Fuhrer, two members of the Gestapo came to his home. He was interrogated and held for several hours, released only after he promised never to lecture or write about the Massacre again. The Siemens company immediately sent him abroad, perhaps for his own protection.

He returned to Berlin, which, like the home he had just left in China, would soon become a city under siege. Rabe’s apartment was destroyed by a bomb. When Russian foot soldiers arrived, all too familiarly, Rabe began to hear of rape and looting, this time of his own people. Still, he wrote that the takeover was more tolerable than that in Nanjing.

“There are worse things”, he wrote. “I saw more than enough of that in Nanking. But, chin up, even if it’s bitterly hard to do! Onward!”

When the war ended, his family fell into poverty. Since Rabe had been a Nazi, he lost his job and was forced into the arduous “de-Nazification” process, for which he had to pay his own legal defence. This depleted his savings and brought his family to near-starvation. In order to stay alive, they ate stinging nettles and acorns, and began to sell his collection of Chinese artwork to the American troops.

He was homesick for Nanjing. “If I had heard of any Nazi atrocities while I was in China, I would never have joined the party”, he wrote. “The ‘living Buddha for hundreds of thousands’ in Nanking, and a pariah, an outcast here!”

In 1948, the Nanjing city government heard of his plight, and announced to its citizens that Rabe was penniless and hungry.

The response was instant and immense. Within days, massacre survivors raised the equivalent, at the time, of US$2,000, enough to keep Rabe alive.

Soon, Rabe received four large packages. Inside, he discovered heaps of milk powder, sausages, tea, coffee, beef, butter and jam. For the next year, the city mailed Rabe a package of food each month.

The parcels, Rabe wrote, had restored his faith in life.

In 1946, after prior rejection, Rabe was granted successful “de-Nazification,” which allowed him to return to his work at the Siemens Company and again earn a small salary. The De-Nazification commission gave one reason for their reversal; Nanjing.

In their verdict, the commission wrote, “Despite your having been the deputy local leader [of the Nazi Party] in Nanking and although you did not resign [from the party] on your return to Germany, the commission has nevertheless decided to grant your appeal on the basis of your successful humanitarian work in China”.

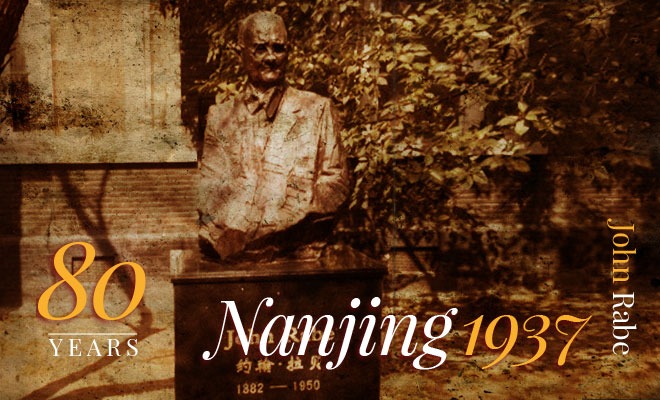

Rabe died a few years later from an artery stroke, well fed and surrounded by family.

For decades, his story was largely forgotten. Although Rabe had kept his diaries meticulously bound and numbered (perhaps because he sensed their historical importance), the books were unseen for over 40 years. Rabe’s descendants worried about the optics of promoting a Nazi’s accomplishments, and they kept the diaries hidden away.

In 1996, at historians’ urging, the family made the diaries public. Rabe’s notes were not only of interest, but also of import; they corroborated other first-hand accounts, and lent credibility to the fact that the atrocities took place, something occasionally under question by Japanese ultra nationalists.

In the end, Rabe’s diaries continued the fight that he had taken up some 60 years prior; a decision to stay with the people of Nanjing, and to make sure they would not be forgotten.