Since this column is dedicated to the discovery and discussion of quirky and unusual Chinese food, it makes it quite the challenge to keep looking off the beaten track, but so worth it. So far, we have had a look at humble everyday staples such as bamboo shoots, lotus root and the Sichuan pepper corn.

Chinese cuisine has evolved greatly over the past 3,000 years into delightful morsels indeed. So this month we’ve had fun shaking off our peasant roots to delve in to the pallet of China’s upper class, primarily imperial cuisine. With Nanjing serving as China’s capital a number of times in its past, I figured at least a few Jiangsu dishes during that time must have made it onto the imperial menu.

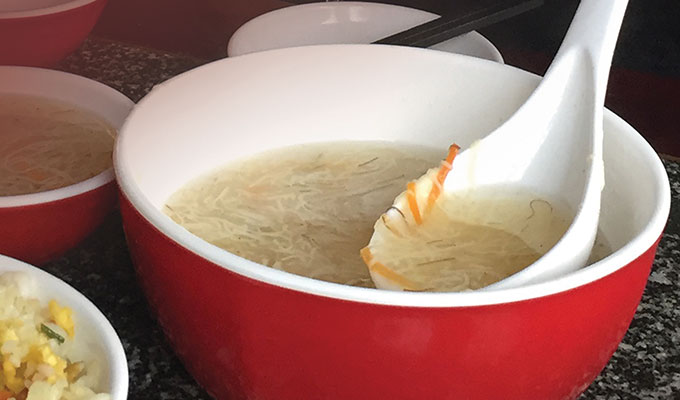

As it turns out Jiangsu’s most famous imperial selection is Wensi Tofu Soup (文思豆腐汤 wénsī dòufu tāng). This fiddly dish showcases the knifemanship of a Yangzhou chef (Wensi), who shot to fame during the Qing Dynasty after the great Qianlong emperor brought the dish back to the palace. The dish is famous for Wensi’s knife skills, as a rectangular block of soft tofu is sliced into no less than 5,000 pieces, along with colourful vegetables; carrot together with cucumber and black fungus.

Nanjing food, while comparing it with the likes from Sichuan, Yunnan or Xinjiang, appears rather, shall we say, bland. Its cuisine actually follows an balanced taste, while the matching of colours is most important. Nanjing food focuses on utilising the Yangtze river, therefore fish, shrimp and duck all featured heavily on imperial dining tables.

Other regions of Jiangsu donating their imperial heavyweights include the sweetness of Suzhou and more seafood delights from Nantong and Wuxi. Cuisine in Nanjing’s northern brother Shandong, known as Lu cuisine, is one of the “eight culinary traditions, and one of the four great traditions” of China, and is celebrated for its light aroma and multiple flavours and styles.

As the birthplace of Confucius, it is also considered the bedrock of northern Chinese cuisine; fine food preparation can be found in Shandong from as early as 770 BCE. During the Yuan dynasty, Lu cuisine spread north and heavily influenced cooking styles in Beijing and Tianjin, which in-turn impacted imperial cuisine. Staple Lu ingredients include maize, peanuts, grains, vegetables and vinegar.

As Qianlong moved north and made his way to the home of Lu cuisine, an imperial favourite was found in Dezhou Braised Chicken 德州扒鸡 (dezhou pa ji), which one can now sample on a high-speed train. Other notable imperial dishes include the infamous Beijing Duck 北京烤(Beijing kaoya), Shark’s Fin Soup (yuchi tang) and Bird’s Nest Soup (yanwo tang). The latter two dishes highlight an important emphasis of imperial cuisine, that of health and longevity.

The imperial diet required the freshest and healthiest of ingredients, and as a result of sourcing the best chefs from around the country, people say that whatever the imperial family have on their table is the best China had to offer during that period. While the best food of the land was reserved for royal mouths only throughout China’s past, nowadays anyone with an interest can pop into their city’s Imperial Cuisine Restaurant and experience first hand what it was like to eat like a king.

In Nanjing we have That Small House restaurant (see review here), serving up delectable imperial staples in a setting that is fit for a queen indeed. Set in a traditional ancient style courtyard, the restaurant allows diners to fully immerse themselves from the moment they step inside.