When the One-Child Policy was introduced in 1979, no one could have foreseen its side effects that would drastically change the face of China, leading to the advancement of women’s position in society.

In the early years of the policy, a new cultural phenomenon appeared due to traditional Chinese values of favouring sons over daughters as they provided higher ROI. Sons could earn money and provide for their parents in their old age under the label of being filial, while women upon getting married were seen as having been lost to the household, even on a legal level. As Yang Li and Xi Yinsheng explain in the Journal of Contemporary China (2006), when it came to land distribution the loss of the daughter meant that a share of the family’s contract land would be returned to their village under the Household Responsibility System first adopted in 1981.

Culturally speaking, a bride and her mother to this day tend to cry tears of sadness on the wedding day, because the young woman is entering her husband’s household and thereby no longer belongs to her parent’s family, although luckily today the situation is not quite as literal. This cultural landscape caused skewed gender proportions following implementation of the birthing restrictions, as parents only had one shot at producing the “worthy investment” of a son; if that one shot failed the solution for many was abortion. A natural gender rate sees between 103 and 106 boys born for every 100 girls. In China in 2004, the gender ratio reached 121.2 boys per 100 girls. In some rural areas of the country, where lower education and conservative views were more present than in urban centres, the skewed ratio even rose as high as 140 men compared with 100 women.

Increased Status for China’s Women

Such a reality has given women considerable power in terms of selecting their husband; with too many men trying to find a wife, the women now have the pick of the bunch and have been able to increase their demands in terms of financial security, looks, character or a combination of these. The classic “buy a flat, buy a car, find a wife” syndrome that is putting China’s male population under immense stress has emerged from this historical development, while the little empresses now have much higher expectations of prospective matches as a result of their increased bargaining power.

Another area in which women’s status in society has advanced drastically is education, for which the one-child law inadvertently has done wonders. With households limited to only one child, all the financial resources that would have formerly been spent on favoured male siblings have been reallocated to girls. Such is the argument of Yuan Ren from the Telegraph. “As a single child born in China myself in the late 1980s, my own father, who back then was less than ecstatic at the news of a daughter, has no less strived to provide educational opportunities for me that beat what most boys of my age and background received – something that could easily have been shifted to a male sibling, if I’d have had one. Today, the narrative of every single child family in China is the same from parents to grandparents, irrespective of gender – how to provide the best for the child,” Ren argued in a biographically inspired article on Chinese women’s status in December 2013.

Higher levels of education in combination with Chinese society’s tendency to let the grandparents handle the rearing of young children, so the parents can go forth and earn as much money as possible to secure a financially stable future for the child, have in turn led to an impressive progression on the career ladder, as a steadily growing number of China’s women are to be found in positions of power.

Emancipation on Paper

While all of this sounds rather positive on the face of it, the emancipation of the “fairer gender” on paper is at odds with the mindset of the nation. To this day, sexism and gender stereotyping are rampant in China, illustrated in no unclear terms by the celebrations of International Women’s Day on 8th March. A particularly graphic headline to be found on one of China’s English news outlets read “Hot moms present flash mob in downtown Nanjing” and goes on to describe how the “beauties” belly-danced in honour of this day. With hardly any sign of a discourse on advancing women’s rights, this occasion has instead been turned into yet another excuse for retailers to launch into a special-offers frenzy, for women to engage in frivolous displays of what is deemed femininity and for men to present the ladies in their lives, i.e. wife and/or mother, with lavish gifts to show their appreciation, reinforcing the image of women as princesses who need their men to shower them with presents for a fulfilled life.

The notion of the “weaker sex” is further indoctrinated by countless restrictions imposed upon young Chinese women in their daily lives because their bodies are deemed too frail to be able to withstand any type of stress. This ranges from not being allowed to ingest cold drinks and food (especially not during her “time of the month”), to not being deemed fit for work that takes place at night and pretty much all but having to come to a complete standstill shortly before, during and after pregnancy (the post-natal month of Yuezi).

Traditionally female care-taking jobs on the other hand experience a sore absence of male presence. Speaking at a press conference during the National People’s Congress on Women’s Day, the Jiangsu delegation pointed to the lack of male teachers in kindergarten as a large source of frustration. While the internationally accepted, recommended average suggests that a proportion of 7 percent of male teachers is appropriate, a figure which is in itself already rather low, in China the corresponding number of male professionals in pre-school education does not even amount to one meagre percent.

Even worse, while women now have the power to be more picky as relates to their prospective partner, once that wedding ring is on her finger, most Chinese women see themselves under the thumb of their husband’s parents, who if traditionally-minded will dictate many aspects of their daughter-in-law’s life. On the most basic level, this often includes attempts to force independent and emancipated females into the role of the housewife into which they were allegedly born. Yet, these are women who not only have the ability to earn money and have a career due to their increasing levels of education; they often have the desire.

More importantly, having been brought up as Little Empresses, with an entire family focused solely on meeting her desires, many young women are used to getting what they want from their immediate families. When all of a sudden they are meant to compromise their personal wishes and their thirst for freedom simply because they are someone’s wife, it is unsurprisingly a recipe for disaster. The contradiction of how these women are brought up and the expectations placed on them later in life more often than not lead to unhappiness and conflict with their in-laws and in the second instance their husbands, sewing the seeds for a failure of the marriage.

The attempts by her new family to control their son’s wife can in some instances even go as far as denying her the right to chose when to give birth. In a recent discussion with a local friend, she revealed the experience of a girl from her hometown; once she was “safely” married, her parents-in-law consulted a fortune teller as to what an auspicious date was for their future grandchild to be born. After deducting nine months, the young woman was informed of the exact day on which she had to conceive. No pressure. The inquiry whether this was a common occurrence even in today’s China was met with a dismayed “Yes, very!”

The irony is obvious; while in some Western countries women are fighting for the right to decide whether they want to carry a pregnancy to term, in China there are still women who do not even get to chose whether they want to be impregnated in the first place. Such realities are a serious smack in the face to any “My Body, My Rights” campaign.

On the legal side, Chinese women have had to suffer further setbacks. While in the past, a woman would have a right to half of her husbands assets upon divorce, recent amendments to divorce laws have ended the tradition of splitting 50/50. Instead, when it comes to property, the person whose name is on the deed or contract will in case of separation remain the sole owner of said property. Since in China it is customary for the deed for property to be solely in the husband’s name, at times even irrespective of who initially provided the money, the new regulation will force many Chinese women to stay trapped in unhappy marriages simply because they cannot afford to leave.

Speaking to the Telegraph a Mrs Zhang, who is currently going through divorce, describes the new law as an insult, which fails to address the contribution and sacrifices women make as wives and mothers. “I think the status of women is even lower than in the old days, when women didn’t work and stayed at home. At least, they were protected then.

“Now, women face a lot more pressure than men in the workplace but their obligation to the family is the same as it was in the old days,” observed Mrs Zhang.

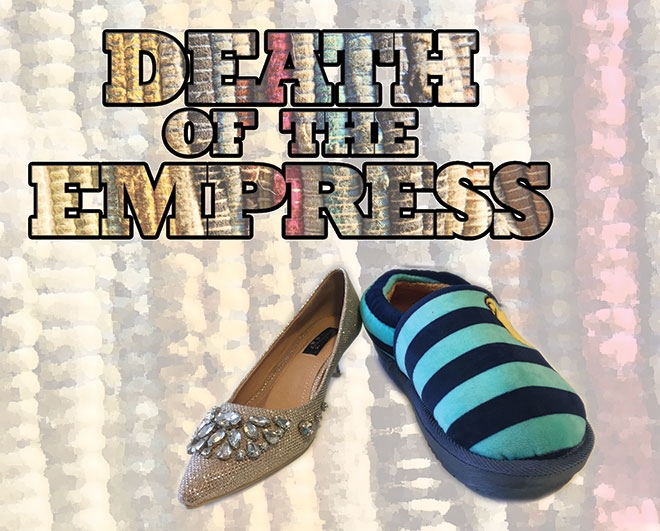

Death of the Empresses?

To make an already less than ideal situation worse, the little empress, who has enjoyed the privilege of being able to chose a higher quality spouse and has received a much better education than ever before in the history of the Middle Kingdom, might soon find herself in danger of being extinct. Skyrocketing property prices and the related financial pressure on parents of young men have led to a reversal in China’s gender preference. Nowadays, families breathe a sigh of relief if their child is born female simply because they cost less money. After all, not only the property involved in finding a female partner needs to be purchased at increasingly unrealistic prices but traditionally the entire wedding is paid for by the husband’s parents, and with higher expectations on the bride’s side plus the necessity to put on a grand show in order to gain face, those weddings are becoming an incredibly expensive affair at an average of ¥200,000, as Mocha Wedding Planning company told China Daily in 2013. This is causing more and more people to conclude that a son simply isn’y worth it anymore.

Evidence for this change of perception can be found in the latest birth rate data. Over the last five years, the gap has narrowed to 117.6, and Cai Yong, a demographer at the University of North Carolina, told Bloomberg that in a decade that number might shrink further to 110. However, a more stable gender ratio comes at the cost of women losing their current power in the marriage market.

In addition, China’s relaxation in 2014 of the One-Child Policy to a Two-Child Policy for parents, where only one person is a single child (previously both spouses needed to be little emperors), might mean that the educational boost the country’s female population has received over the past decades could implode as parents are once again forced to chose which of their offspring should receive the better education.

It is a matter of speculation whether Chinese culture has progressed enough to allow women to maintain their educational advancement if pitched against a male sibling. It seems China’s empresses are in for a rough time if they want to cling onto their throne; let’s hope they are tougher than society gives them credit.

This article was first published in The Nanjinger Magazine, April 2015 Issue. If you would like to read the whole magazine, please follow this link.