Vintage wine may be a treasure worth preserving, but should vintage traditions be preserved in the same way as well? It is no doubt that digging up a bottle of wine buried for decades, immersed beneath layers of soil, dirt and life, is an intriguing concept, but what does this vintage wine tradition really mean when stripped bare?

Over the millennia, Chinese spirits and liquor have occupied a special place in many of China’s greatest figures, inspiring praise from scholars and comforting the lonely and the miserable. Classical Chinese poets were so captivated by it that they wrote countless poems dedicated to the beauty of wine. Li Bai, one of the most celebrated poets in China, probably would not have produced so many poems if he was not constantly intoxicated.

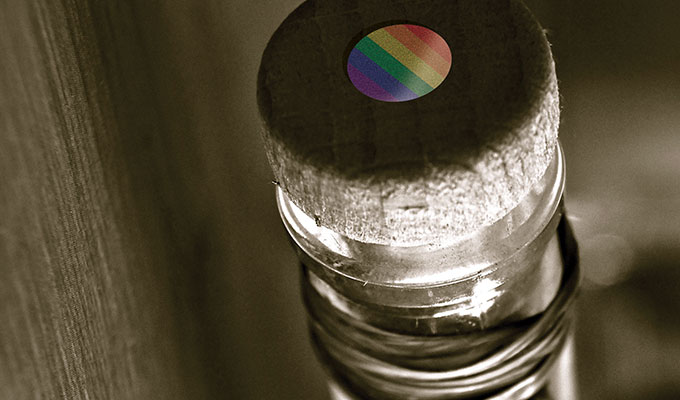

But one special type of rice wine is rarely heard of today. The “Nu’er Hong”, or directly translated to English, the Red Daughter wine. So, it happens that, traditionally, Nu’er Hong bottles of wine would be buried upon the birth of a daughter and would be left undisturbed until the daughter marries. Then the bottle would be unearthed on the daughter’s wedding day. However, perhaps with a bit more digging, we can find remnants of it that are not quite so beautiful in their cores.

This tradition dates back to the Jin Dynasty and even earlier, when parents brewed rice when a baby girl is born and buried a jar of wine under osmanthus trees in their backyard. This wine was traditionally opened on the daughter’s wedding day to celebrate her becoming of a young woman and to subtly let out an 18-year-old held breath, terrified that their daughter would never marry off; re-establishing the belief that in ancient China, girls were just another mouth to feed, and a commodity to be shipped off when the time was right. When a boy is born, parents brewed the same rice wine, called “Zhuang Yuan Hong”, or “Scholar Red”. This wine was meant to celebrate the academic achievements of the boy, as only men could take imperial examinations.

China is known for its rich history and culture, but it is time we let go of obsolete, traditional beliefs that prevent people from attaining what Chinese liquor represented in the first place; a celebration of life. Even today, despite a historically relaxed view of homosexuality, China is known for her reluctance to embrace gay rights. When Taiwan legalised gay marriage on 24 May, 2017, the official media over the Strait in China reacted with a barely stifled yawn. Only one State-owned, English-language newspaper took notice of this revolutionary decision. The more widely-read Chinese versions and other television and news outlets ignored it. In Chinese poetry of the 9th century, commonly recognised as the golden age of Chinese literature, it is often difficult to distinguish if a love poem is addressed to a woman or man. Unlike Christianity and Islam, Chinese religious and social thinking does not harshly condemn same-sex relationships.

Homosexual relationships were regarded as neither good or bad in Taoism, while Confucianism was sometimes thought to have indirectly encouraged it by perpetuating close relations between master and pupils. One of the greatest novels in China written in the 18th century, “The Dream of the Red Chamber”, features both heterosexual and same-sex relations. Moreover, in 1997, homosexuality was legalised in China, whereas before it could be prosecuted under a law banning hooliganism.

Yet, only in 2001 did the Chinese government remove homosexuality from the health ministry’s list of mental disorders. As with almost every other flourishing stigma in China, an explanation for this lingering disdain traces back to the traditional patriarchy steeped in Chinese history. Filial values remain strong in China; sons are considered vehicles for carrying on a family’s good name and painstakingly cultivated reputation, and are supposed to marry and have sons of their own.

This almost ridiculous obsession with producing sons has converted Chinese families into a sort of bastion against homosexuality. In 2016, on behalf of the UN Development Programme, Peking University’s sociology department carried out the largest survey of attitudes to, and among, homosexuals and other sexual minorities. The survey demonstrated that 58 percent of respondents (hetero and homosexual) agreed with the statement that gays are rejected by their families, a higher level of rejection than occurs at work and school. Fewer than 15 percent of homosexuals remain closeted, in fear of their parents finding out, and more than half of those who did come out reported that they had experienced discrimination as a result.

We owe it to ourselves, and the next generation, to realise that love is purely the only treasure worth preserving forever; that it is the only vintage that truly ages beautifully. It is time for China to recognise that you don’t have to be the son to be the sun. As clichéd as this saying is, it is also brimming with untold, profound truth. Life is too short to be wasted on not loving. As the great poet Rumi penned, “Love is the bridge between you and everything”. We cannot possibly build this bridge without appreciating and accepting everyone; men and women.

So, the next time you open a bottle of wine, whether it’s Nu’er Hong or not, raise your glass and celebrate the youth, for they are brave. They are bruised. They are loved. They have been underestimated by history itself, and they have been hiding in the shadows for a millennium, afraid of the smoke.

Perhaps the “Red Daughter” takes on a new significance; it marks the beginning of an era, a time for Chinese women to step out in our magnificence. No more fearing the fire; it is time to become it. It means finding our own heartbeat, and rising. Dare to show the glory within us.