Today, likely at around 10 am, and continuing for quite some time, an urgent cry will ring out across Nanjing. The air raid sirens that warned local people of incoming Japanese bombers will once again wail, as they do on this day every year.

Cars will idle in the streets. Barges on the Yangtze will blast their horns. And people across the city will pause their daily toil to mourn the slaughter that began on this day, 80 years ago.

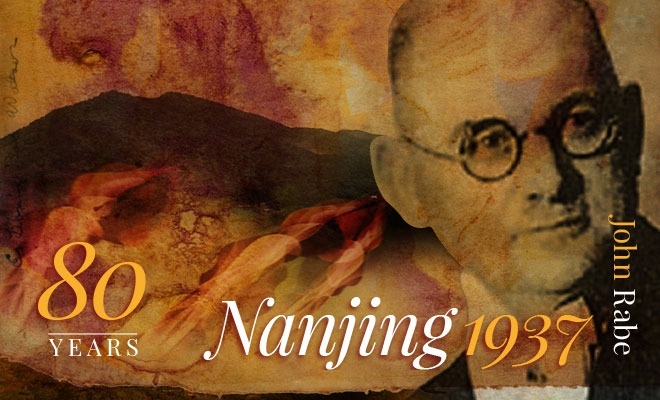

Consider, for a moment, the scene unfolding that day before the eyes of a German expat who stayed to help during the 1937 Nanjing Massacre, then known worldwide as “The Rape of Nanking”.

On the eve of 13 December, 1937, artillery fire rang, incessantly, from Purple Mountain. Suddenly, the hill was engulfed in flames. The Japanese were on Nanjing’s doorstep.

John Rabe, a sarcastic Nazi who spoke almost no Chinese and worked as an electronics middle manager in Nanjing, was in his house, packing a bag of first aid supplies.

Rabe, unexpectedly and improbably, had just become the most powerful civilian in Nanjing.

Months earlier, Rabe decided he could not abandon the Chinese mechanics and engineers he employed at the Nanjing branch of Siemens China Company. After all, Rabe had lived and worked in China for nearly 30 years. It was home.

After Rabe learned he was one of the few foreigners who planned to stay through the siege, he reluctantly agreed to become chairman of the International Safety Zone Committee, a group tasked with establishing a safe zone for refugees.

Rabe partnered closely with the mayor of Nanjing to establish this safe zone, but after the mayor and other government officials fled the city, and the Chinese military and police had retreated or were killed, Rabe became the de-facto leader of the city itself.

As early as the prior summer, Nanjing civilians flocked to Rabe, as if he carried a magic talisman to ward off danger. With each air raid, Rabe’s self-dug backyard trench became more and more crowded. Packed in beside him were his coworkers, servants, neighbours, mailmen and all their wives and children. Rabe even decided to admit his cobbler, with whom he had had a long-standing rivalry (the cobbler, evidently, had up charged him on a pair of boots).

These interlopers occasionally vexed Rabe. After a heavy-set man sat in the centre of the trench (the safest part), Rabe posted a passive-aggressive note at the dugout entrance, demanding that only women and children sit in the centre (Rabe himself always sat near the edge). Still, despite his grumbles, Rabe never turned anyone away.

On 12 December, knowing the Japanese were about to take the city, Rabe grabbed some bandages and ran thoughtfully through the rooms of his house, as if he were saying goodbye. At the last minute, he saw photographs of his grandchildren and tucked them into his bag.

Even then, his trademark gallows humour was intact. Every morning and night, he would pray, “Dear God, watch over my family and my good humour; I’ll take care of the other incidentals myself”.

But the next few days would be filled with a horror he had never known, and the events of that year would change his life forever.

History doesn’t look kindly upon Nazis, but Rabe’s status as the leader of Nanjing’s Nazi party is precisely what allowed him save so many Chinese lives during the massacre.

At the time, World War II had not begun, but the Japanese had warily allied with Germany. Once the Japanese entered the city, Rabe said, he could simply shout, “Deutsch”, or, “Hitler”, and the soldiers would snap to attention.

Rabe spent his days in a nightmarish whack-a-mole style pursuit of marauding Japanese troops. His physical presence ensured the safety of the Chinese, so he raced from one impending rape or murder to the next, praying that he could intervene in time.

“You hear of nothing but rape”, he wrote. “If husbands or brothers intervene, they’re shot”.

On the first day of Japanese occupation, Rabe chased Japanese soldiers out of his yard, which was then crammed with about 600 hundred refugees, and he was immediately called to his neighbour’s house to ward off another soldier on the brink of rape. He returned home to find yet another rape in progress. When the constant violence made a woman ill, Rabe sent her to the hospital, only to learn the nurses were being raped as well. He was a force of one against swarms of thousands.

Meanwhile, the remaining Chinese soldiers flocked to clothing stores, spending their last cent on civilian clothes to disguise themselves after the city had fallen. Rabe watched them change clothing in the streets and vanish into the city.

In the end, most soldiers were discovered. Rabe wrote that he watched the Japanese tie up “some thousand” Chinese men in an open field, and looked on helplessly as small groups were led away, forced to kneel and shot in the back of the head.

According to the Chinese government, more than 300,000 people were murdered during the Nanjing Massacre, many of whom were civilians, murdered in the most torturous ways imaginable; people were stabbed with bayonets and set on fire; bodies were raped and mutilated.

Rabe’s former porter was shot, for seemingly no reason at all. Rabe wrote, “His old certificate of employment, issued by the German embassy, lies before me drenched with blood”.

For the next two months, Rabe managed the Safety Zone, which was soon packed with 250,000 refugees, more than he anticipated in even the worst-case scenario.

He spent his days roaming the city, trying to prevent rapes and murders, even once physically lifting a soldier from atop a young girl. He hid hundreds of women on his property and armed them with whistles to call him if a soldier ever entered. Nanjing citizens started calling him “the living Buddha of Nanking”.

Yet, while these Chinese hailed him as a deity, Rabe was decisively human, and irrefutably, a Nazi. He once telegrammed Adolf Hitler to request aid, though the Fuhrer never responded. “By God, I hope Hitler helps us”, Rabe wrote.

Scholars have argued that, at the time, Hitler’s anti-Semitism was treated lightly in the international press, and Rabe may not have understood what was happening in Germany. Some suggest he was drawn to the Nazi party for a sense of community abroad.

Rabe later wrote of the genocide, “It was our impression that any ugly stories were just rumours, nothing more than enemy propaganda, especially, since as I’ve mentioned, no one could say that he had seen the atrocities he was describing with his own eyes”.

But in 1938, Rabe would have understood the anti-Jewish Nuremberg Laws, and his diary reveals anti-Semitic tendencies. He used common racial stereotypes and suggested a German-Jewish chauffeur driver had no right to bear a swastika on his car.

And yet, inconceivably, Rabe was the man who watched over the peace zone in Nanjing, while dozens of other internationals fled. He wrote that he stayed for no other reason than sense of duty and reverence for human life. Indeed, he saved hundreds of thousands.

During the summer, Rabe wrote, whenever a Chinese anti-aircraft gun downed a Japanese bomber, gleeful applause erupted from the trenches. Stoically, Rabe touched the brim of his hat and muttered, “Hush. Three men are dying.”

Tomorrow, read about the irreversible effects of war. What happened to Minnie Vautrin after she left Nanjing?