While understanding China’s consumer culture is certainly a scholarly fashion, and “to get rich is glorious” (Deng, 1992), that contentment has forever been rooted in external endorsement is far from being unique to the Middle Kingdom.

For China’s growing materialistic aspirations and interest in luxury products have little to do with her traditional cultural values and are no less political or ideological social constructs based on the wavering guidance of Mao and Deng than they are mere traits locked into the core of humanity.

The first iPhone 6 I saw in China was sported by a foreigner. A couple, in fact, and they each had one. And they were both the Plus model. Granted, they had probably just stepped off a plane but, given the theme of this issue, it points to a scenario that exists in Western countries not fundamentally different from that here in China. We are, therefore we aspire. Constantly. We aspire toward owning material possessions since we believe they enhance our experience and quality of life. We believe our problems will no longer trouble us or at least be greatly alleviated should we have these material possessions. More money means more of the means to get more of the things we want.

The very fundamentals of materialism are a Western construct. Our consumerist society has its roots in the economic growth experienced in the US and Europe after the end of World War II, fuelled by the technological advances made as necessities of the war itself. Thus, the West discovered materialism while new industries such as mass media and marketing saw a goldmine, and got digging. When the pit runs dry, it is time to trigger a new wave of consumption. And what do you know? We purchase these new products to be happy and discard our old ones. As the aforementioned couple, or any serial iPhone owner will tell you, materialism is a catch 22 situation that demands we seek more material items as soon as the the short term satisfaction of our most recent purchase dissipates.

In the 1958 book “The Affluent Society”, Harvard economist John Kenneth Galbraith articulates that new demands (non-organic, i.e. non-essential to human existence) are created by advertisers and the “machinery for consumer-demand creation” that benefit from increased consumer spending, leading to the dependence effect, a process by which “wants are increasingly created by the process by which they are satisfied”.

In such ways, the last two decades in China have mirrored the postwar of the West. Back in 1993, when I arrived in Shanghai, there was little advertising that was not more accurately termed “propaganda”. People lived simply and were, on the whole, not very well off; they had barely any money, yet there was not much worth buying anyway. Shortly before my arrival, the British journalist and television broadcaster Alan Whicker made a trip to China, and in Shanghai quipped that the shops had nothing that one wanted to buy, but were full with everything that one did not want to buy. Nevertheless, the Chinese people were arguably more content than they are today. Materialism lies at the root of this discontentment.

This was a time when people were bereft of illusionary beliefs over possessions. Very few looked upon a car as a bridge to an idealised life, since there were hardly any cars that weren’t taxis, or owned by the government or the military. It was next to impossible to buy a house and so that was not going to increase anyone’s happiness. Nobody was seeking to boost their confidence with image enhancing electronic devices, because there were none to be had. Likewise, people did not feel they would be more worthy, or more attractive, with a leather handbag from Italy as the marketeers of consumer goods had yet to create the necessary aspirational images.

How times have changed. Here in 2015 China, it is not just about buying it; there is also flaunting it. Again however, the trend is nothing new. The term “conspicuous consumption” dates back to 1899 when it emerged in the book “The Theory of the Leisure Class” by American economist and sociologist Thorstein Bunde Veblen. Therein, the term is ascribed to the behaviour of people of “new money” who emerged during the Industrial Revolution of the late 19th and early 20th centuries and their efforts to manifest power and prestige through a very public accumulation of wealth. We know them well; they were the obnoxious ones on the Titanic.

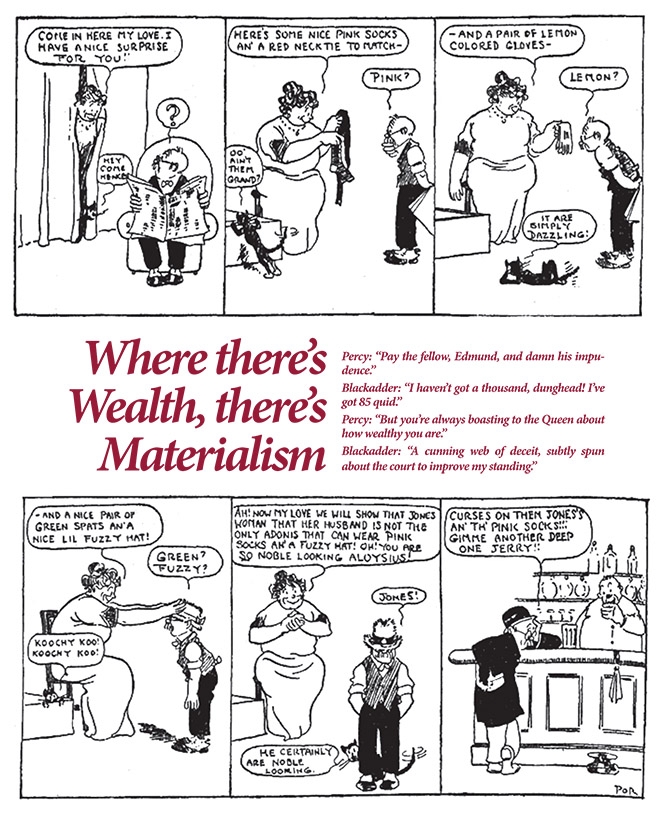

Perhaps no better proof for the global nature of conspicuous consumption can be found in the expression, ”Keeping up with the Joneses”, popularised as the name of a comic strip that first appeared in 1913. Through it, society learned to draw comparisons with our neighbours; the first social benchmarking that measured our standard of living in relation to that of our peers. The expression even lent its name to the 2009 movie, “The Joneses” starring Demi Moore and David Duchovny with the theme of stealth marketing to relieve suburban boredom. Just as in China, social status in Western countries once depended on one’s family name. Consumerism changed that, and social mobility was born. As desirable goods became more available, so evolved a natural tendency for people to define themselves by what they possessed. Conspicuous consumption and materialism have been an insatiable juggernaut ever since. It would appear that China is further in line with Europe or the USA in so far as people who are unable to keep up with the Joneses may become dissatisfied with their lives. A 2010 study carried out by researchers at the University of Warwick and Cardiff University sought to correlate why, over the past 40 years average incomes have risen enormously, and yet people have not become any happier. By analysing data from the British Household Panel Survey (BHPS), the team found that life satisfaction from a financial income standpoint is comparative; to be happy, people need be able to perceive themselves as earning more than friends, colleagues or the Joneses.

Where China is different to other countries is in so far that materialism does not appear to wane with age. Younger people (those under 40) the world over spend greater amounts of time out shopping with friends, checking out the latest fashionable must haves, aspiring after material goods such as sports cars, a villa in which to live, desiring of more money and becoming better off.

Eventually, the majority of us see the wanton greed for what it is, and start sounding off with expressions such as “you can’t take it with you when you die”. In China, not so. Here, the older generations are as enthusiastic a purchaser of smart phones as the younger hipsters. Visit any apartment or villa showroom in China and there will be just as many grannies nosing in the cupboards as newlyweds. Furthermore, being of such an age in China has only strengthened their belief in conspicuous consumption as the holy grail of symbolic wealth.

Another aspect of materialism that is unique to China lies in its excesses. From fast trains to selfieing, so the advertising and promotion industry too excel in shamelessly feeding the populace symbols of hope, happiness and joy, within a framework that is often only loosely regulated. In fact, the present advertisement law of PRC has remained unchanged since 1995. Fortunately, an amendment to the law should be passed at anytime. Yet, the tricksters have since been having a field day, feeding the materialism frenzy by running amok in a virtually ungoverned environment; how else can a male pop star end up promoting female sanitary products?

Once again, China is little different to other countries; provided the government gets out of the way, people are free to overdose in any way they feel fit. If that means a spending war between themselves and the Zhangs and Wangs who live down the street, then so be it. Yet, once our squabbling teenagers grow up, it is odds-on that materialism will in the next 20 years take a back seat in China, as it has done elsewhere, especially if the economy begins to falter. In some aspects, the writing is already on the wall; a study undertaken by New York-based advertising agency TBWA between 2002 and 2009 suggested that the appeal of traditional values such as loyalty, moderation and respect for elders had received a higher standing in many people’s consciousness whereas material and aspirational motifs such as personal success had declined in importance.

Stepping in to fill the future void left by the departure of materialism will come, we all hope, something that brings longer lasting happiness. Perhaps that’s what Confucius was on about in the first place; Blackadder could do well to pay attention.

This article was first published in The Nanjinger Magazine, March 2015 Issue. If you would like to read the whole magazine, please follow this link.