Foreigners in China can be forgiven if the events of 2012 left them feeling just the teensiest bit unloved.

From Yang Rui’s rant about “foreign trash” to stricter restrictions on visas, international residents here were feeling the sting of their “laowai” label more than usual. While we could answer with a rant about how insensitive modern China can be or how some foreigners can spoil it for the rest (and you know who you are…), we’ll take on the whole “laowai” sensation from a more sober perch.

To fully grasp the loaded topic of “outsiderness” in China, it helps to go back to the ancient scholars and myths that first coloured Chinese perceptions of the “foreigner.”

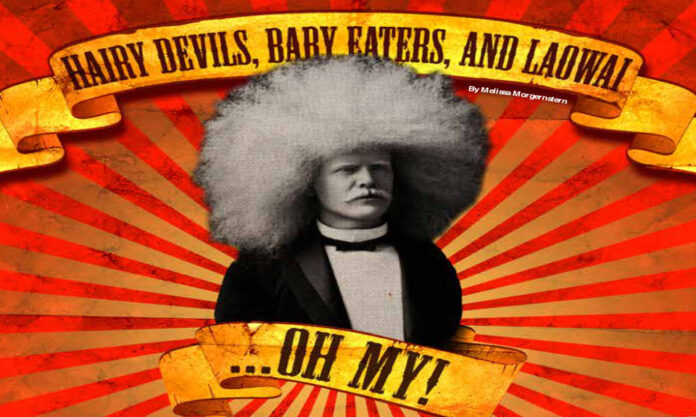

Hairy Devils and an Upside Down Civilisation

Abrupt Entry = Lifelong Ambivalence

It cannot be denied that China’s history is deep, rich, and complex. But the country’s long held view of itself as the centre of the universe and civilisation met with a rude awakening when Europeans made it to China, bringing their influences with them. Some might say that the realisation by Chinese intellectuals of civilisation from outside the “central middle kingdom” produced near-trauma by puncturing their view of China as the centre of the modern world. This became the basis of the reigning notion of non Chinese being outsiders.

While China long held the outside world with deep suspicion, major treaties and historical events, such as the 1729 Chinese Anti-Opium edict, which enabled the British East India Company to flood China with opium, and Article 156 of the Treaty of Versailles, which led the Germans to transfer Shandong to Japan, also fed a more negative general view of the foreigner.

In China, history and betrayal are not easily forgotten.

Also playing into China’s view of foreigners are local definitions of elitism and bias based on ethnic origin, language differences, religious belief, or social class. While China is home to a highly developed, mod- ern society, traditional prejudices remain. These prejudices are not only geared towards foreigners or minorities; they also exist within the majority population.

The general trend is that those who are “developed” or “modern” tend to receive more deference while those seen as “backward” or “old-fashioned” are held lower on the social pyramid. Chinese elitism and bias is based heavily on personal and communal accomplishments and social standing.

The bursting of the Chinese intellectual bubble, aggravated over the years by opportunistic treaties and local discrimination has led to a centuries-long ambivalence towards the non-Chinese population of Mainland China.

As Western European influence began to seep in, Chinese people sought to understand the “foreigner” by way of homegrown Chinese thought.

Europeans were first seen as crude, lustful beings, ignorant of Chinese ways and values. During and after the Opium war, foreigners were taken to be cunning, intelligent and completely unpredictable. Foreign missionaries were alleged to dine on babies and came to be viewed as hairy monsters with intensely bad breath. Some intellectuals theorised that foreign power was simply another form of Chinese scholasticism. An admirer of Western technology and reformist named Wei Yuan claimed that European power grew out of a translation and separate interpretation of the Confucian classics into Latin. According to Wei, Confucian literature was so influential that it helped Jesus to establish Christianity.

There are also journals from Guo Songtao and Liu Xihong, two of the first Chinese ministers who were sent to London, in 1876, to learn more about this alien civilisation known as Europe.

Liu Xihong was very conservative in his writing, yet exemplified the bewilderment over Western customs quite clearly. Liu saw everything in England as the opposite of China.

He theorised that this upside-down relationship stemmed from the fact that England is situated south of the centre of the earth: “That is why their customs and systems are all topsy-turvy,” he surmised. Liu posited that this explained why day and night were reversed. So, the next time you feel jet leg, see if doing things backward might help you get over that first-day-back- in-China hump.

Language Shapes Your Thoughts

Mainland foreigners are more than familiar with the phrase “lao wai (老外),” or, for those in Cantonese-speaking areas, with “gwai lo (鬼佬).” These terms reflect a deep spiritualism and a traditional sense of being at the centre of things that remain pervasive in modern society. The term “gwai lo” can be literally translated as “ghost man” but has also been translated figuratively as “foreign devil”. The term “gwai lo” first appeared in the 16th century when European sailors were becoming increasingly prevalent on China’s southern coast.

The negative connotation term was reinforced by fears of Chinese borders being continuously invaded by “uncivilised tribes” from distant lands.

During the Opium war and after the signing of disadvantageous treaties, the terms “gwai lo” (in Southern China) and “yang gui zi” (foreign devil) became a staple of the Chinese language.

Traditional Myths Turning Into Modern Stereotypes

With the Communist takeover and near-abandonment of traditional thought and superstition, many myths about foreigners have been turned into more modern- based biases. Many of us have encountered the flippant comment or unspoken belief that all foreigners are rich, alike and are here to teach English. Tumble on your bike and people nearby will gawk, but may do nothing to help.

Indeed, Chinese society can offer a perplexing mix of friendly warmth and wary chill. There are days when China feels to a foreigner like a welcoming cottage, em- bracing with its tea and noodles, and others when people seem to offer only spiny glares. But like much else of Chinese thought, myths about foreigners have a long and complicated history colouring life here to this day.