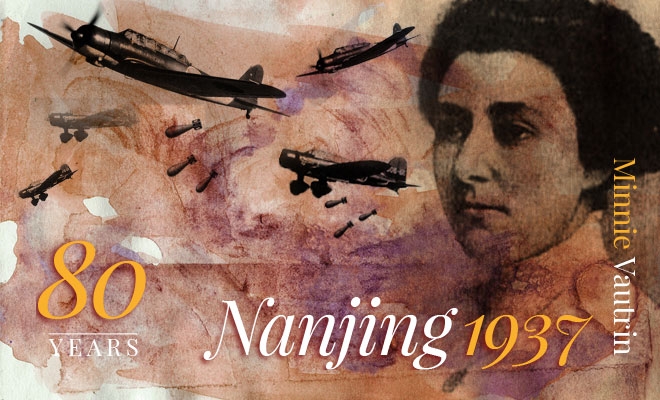

Minnie Vautrin’s mission was to educate the girls and women of China, and she was well suited to that task. History, however, will remember her, not for the women she educated, but for the lives she saved during the horrors of the Nanjing Massacre.

Vautrin grew up poor in rural Illinois, in a time where few women went to college. Against long odds, she worked her way through university and graduated with honours. She decided to forego marriage, turning down her many male suitors, and moved to China as a missionary.

She ultimately became head of the Education Department and dean of studies at Ginling Women’s Arts and Science College. Her goal was to train the next generation of female teachers.

Soon, Nanjing became her home. When her father died in America, she mourned from afar. And when the Japanese arrived, there was no question that she would stay.

Minnie Vautrin was a college dean, and later, a saviour. She became known to Nanjing residents as “Goddess of Mercy” (观音菩萨) for her work during the massacre. Vautrin protected thousands of women from rape and murder, but it was the violence she could not stop that would haunt her for the rest of her life.

During the summer of 1937, as the invading Japanese army moved near, Vautrin watched her bustling capital city prepare to become a battleground. People left by the thousands; those who were too poor, or too stubborn, stayed. Vautrin, at the time 51-years old, purchased fire extinguishers, dug trenches and learned to make anti-gas chemicals.

During this time, her nervous energy was matched by an equally strong positivity, marked by careful notes in her diary. She wrote about the bushels of apples she shared with coworkers, the white and cerise crepe myrtle trees that blossomed throughout the city, and a beautiful young “June bride” whose wedding she attended.

She wrote about the prayer meeting she diligently joined at 7 each morning, no matter how many hours of the previous night she had spent huddled in a trench while Japanese bombers hummed overhead.

Even while sitting in that muddy, mosquito-filled trench, Vautrin marvelled at the city. “The recompense for me these nights”, she wrote, “is always the exquisite beauty of the silver moon, the clearness of the starry heavens and the waving of the graceful branches of our weeping willow trees”.

But as the Japanese foot soldiers drew near, joyful observations vanished from her daily notes. Instead, she wrote about encounters with Chinese soldiers wounded in nearby battles.

After she treated one man’s open wound; his leg had been blown off below the hip, she tried and failed to wash away the scent of his rotting flesh; she used Lysol, soap, cold cream and perfume, but the odour, she wrote, she could never forget.

By late October, she had come to fear the full, silver moon. During nightly bombings, she fantasised about turning the moon off. She wished for nights that were dark and buildings that were invisible to the incessant, plunging “J-planes”.

“May soon the day come when the beauty of the moonlight will not be marred by this passion to destroy and devastate”, she wrote.

As early as August, Americans were asked to evacuate Nanjing. Vautrin refused.

“I feel that my 18 years in Ginling and 14 years in this neighbourhood enable me to carry certain responsibilities which it is my duty to carry on”, she wrote. “Men are not asked to desert their ships when they are in danger, and women are not asked to leave their children.”

And so she stayed. By 13 December, 1937, the Japanese were inside Nanjing.

Tomorrow, meet John Rabe, the Nazi who stood up for human life.