For such an influential and famous artist, Andy Warhol was in fact a rather shy and quiet figure. His subjects, on the other hand, were not. Marilyn Munro and Elvis Presley made some of his most iconic portraits, reflecting the artist’s fascination with all things famous, spelled out in flashy blocks of bold colour straight from a child’s paint box.

Amidst a mushrooming pop-art movement in the 1950s and 60s, Warhol and his peers challenged the idea of fine art by using images from mundane life and popular culture to create pictures, an idea that shook the art world of Britain and the US.

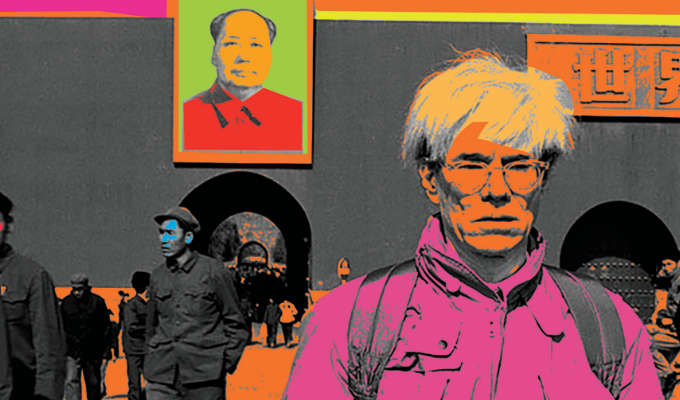

Obsessed with reproduction, he used a special silkscreen process to transfer photos onto canvas allowing him to churn out one image after another, be they Brillo pads or Campbell’s Soup cans, and later even portraits of Chairman Mao.

The pending visit of US president Richard Nixon to Beijing in 1972 sparked nationwide curiosity towards an otherwise mysterious and isolated country. Warhol was no exception. “I’ve been reading so much about China”, the artist said, “The only picture they ever have is of Mao Zedong.”

With China fashionable in the States, and Chairman Mao fashionable in China, the ubiquitous Mao portrait was the perfect subject for Warhol’s next series; a true contemporary icon. Yet, despite making over 400 versions of the Chinese leader, Warhol perhaps never imagined he would see the great portrait for himself, until a decade later standing in Tian’anmen Square he looked up in awe; “Gee, it’s big!”

Warhol had been invited on a “disco trip” in 1982 by the young businessman, Alfred Sui, who was opening a new club in the then British colony of Hong Kong, for which he had commissioned Warhol to make portraits of Prince Charles and Princess Diana. There was time too, for a trip to Beijing and a small crew was assembled to make it into a documentary.

But Warhol in China was not Warhol in the US; the controversial, cutting-edge artist always at the centre of attention. He was simply a snap happy tourist who ripped through film like as if making a flick book of his Asian adventure.

Warhol was utterly enthralled by the world around him; a playground of repetition, quantity and quirk. “I like this better than our culture. It’s simpler. I love all the blue clothes. Everyone wearing blue. I like to wear the same thing every day.”

And that he did. Blue jeans, white shirt, jumper, tie and jacket; Warhol kept the same clothes on for 10 days, even to sleep. Perhaps less inspired by Chinese fashion, however, than he was afraid of the questionable hygiene at his hotel, which was apparently full of cockroaches.

The photos of his visit to Beijing reveal a more personal and endearing side to this household name. As filmmaker, John Alper, recounts in an article on Artsy, “He was very, very quiet. We were all aware that he was kind of introverted”.

Used to being voyeur rather than subject, he relied heavily on his friend, Christopher Makos, in this uncomfortable situation. When everything was set up to film in Tian’anmen Square, Warhol was asked of his impression, to which he turned to his friend; “Christopher, what should I do? What should I say?” Makos looked around and said, “Andy, why don’t you say, ‘The big light poles look like giant disco lights?’” And Andy said just that!

In the radically different world of 1980s China, Warhol was an anonymous traveller, eye catching only for his foreign and rather eccentric appearance. Yet, the enduring pop-art movement that he spearheaded would eventually reach China and become a major theme in contemporary Chinese art of the post Mao era.