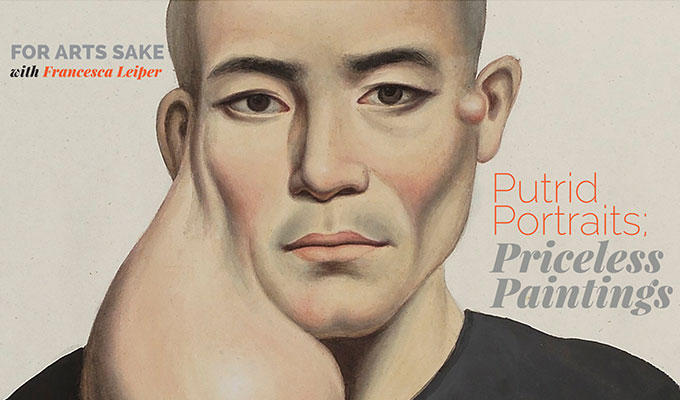

The face is a picture of calm – dark eyes with a soft yet confident gaze, cheekbones accentuated by a warm pink glow, glossy skin and the stubble of what would be thick hair. A healthy looking man, were it not for the drooping balloon of fleshy mass that stretches the skin from his right ear, hanging like an oversized pendulum from his face.

This man was a patient of Peter Parker’s, an American medical missionary to Canton in the 19th century. Sat peacefully despite his oversized tumour, he is an unassuming subject who probably did not anticipate he would be crystallised in painting for centuries, only to be gawked at by one generation after another.

Peter Parker’s pickled paintings,

Cause of nausea, chills & faintings;

Peter Parker’s putrid portraits,

Cause of ladies’ loosened corsets;

Peter Parker’s purple patients,

Causing some to upchuck rations;

Peter Parker’s priceless pictures,

Goiters, fractures, strains and strictures;

Peter Parker’s pics prepare you,

For the ills that flesh is heir to.

The portraits were painted by Parker’s colleague Lam Qua, an artist better known for his western style portraits of wealthy Chinese and foreign merchants, seated among props that speak of their pomp and prosperity. Lam Qua also produced several hundred medical portraits, no less eloquent in capturing the likeness and emotion of their sitters, but existing in a world far removed. A world of the weird, the grotesque and the intensely fascinating.

Parker set up a hospital initially for eye treatment, but soon found himself admitting patients with a whole host of ailments that Chinese medicine could not cure. Lam Qua documented these patients as they arrived in swathes, sporting large tumours from the bulbous to grotesque, and even comical. They came seeking a miraculous foreign cure, an end to their suffering – not to sit for a painting.

But that, it seemed, was part of the treatment. Obsessed by the freakish forms, Lam Qua systematically recorded each patient’s growth to which Parker added commentaries. Together they produced an invaluable medical resource for students then and now, offering a glimpse into conditions that are easily treated today.

The paintings however are much more than just clinical documentation; they tell a complex story of each sitter, just days ahead of what would have been excruciating surgery before the use of anaesthesia. Despite such imminent trauma, his subjects are invariably stolid in expression. Their lack of emotion is almost eerie, in stark contrast to the enormous fleshy forms that swell from their bodies, in some cases as large as a baby. Shiny and permeated with veins, they make us wince. But we are invited to stare, and we want to.

As a body of work, the paintings represent a social class who were not otherwise deemed worthy of the lustrous and expensive oil paints they are described in. They are not portraits of an idealised individual, nor are they simply photographic specimens either. They are real people, each with their own jobs and families to feed, alike only in their disabilities that would have caused great hindrance to their lives.

In almost two centuries the paintings have been viewed by thousands of people from patients and medical students, to the archbishop of Canterbury and the king and queen of France. Even today they are regularly requested for viewing at Yale Library where they are collected, proving the enduring power of these “pickled portraits” to fascinate and beguile, far outliving the men, women and children depicted in the paintings themselves.