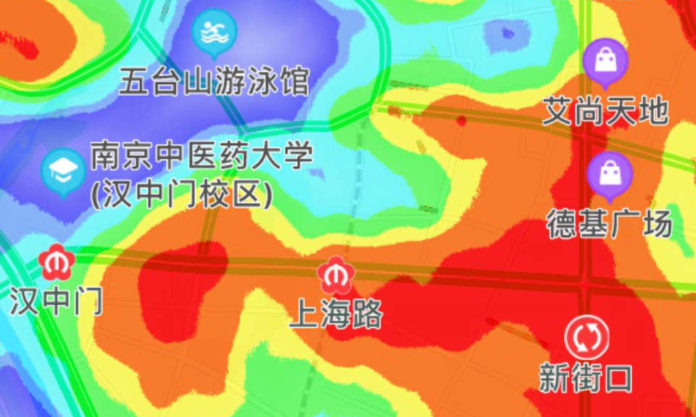

It’s 22 February, 2020, and Xuanwu Lake has just reopened to the public after a long spell of closure in attempts to control the spread of the novel coronavirus. I open up Baidu Maps to suss out the best route and find them not to be the usual grey, but rather a panoply of colours, like oil spilled on water. Red blotches indicate areas with a high density of people, which gradually flood through orange, yellow and all the colours of the rainbow to purple. That’s where I find myself, in one of the quiet spots.

It’s a nifty feature, and the child inside me is drawn to the multi-colour shapes that continuously morph throughout the day. But for all its colourful vibrancy, this version of a Nanjing map, somewhat ironically, marks a rather less colourful time to be staying in China.

- Chinese Food Rocks; Art as Food, Food as Art

- A Royal Success; The Largest Exhibition of Chinese Art Ever

- China Design Icons 101; A Lowdown on Chinese Logos

Maps are one way in which we visually process and understand the world around us. We often think of them as objective and accurate, but in fact they conceal just as much as they reveal. They may be useful tools for navigation, but equally they can be made as propaganda, as works of art or fanciful imaginations of non-existent worlds.

If you look at a world map in China, you’ll find the Middle Kingdom is placed front and centre, with the “West” sat on what appears the eastern half of the map. Who’s to say where is east, west or middle, but this simple example demonstrates how our different views of the world are manifest in maps.

The earliest painted world map in China follows the above format, although interestingly, it was made in collaboration between the Italian Jesuit missionary, Matteo Ricci, and Ming dynasty official, Li Zhizao. The map exists in several later copies, one of which can be seen in a large reproduction at Solar Villa (Mingshe Puzhai) in Nanjing. Around the main image, additional maps and diagrams explain the logic of other astrological phenomena, such as solar eclipses and how to calculate the 24 solar terms; ideas that would change the Chinese people’s understanding of the universe. Combined into one huge painted image, this map in many ways represents the merits of cross-cultural engagement at that time.

Maps of what we now call Nanjing were made from as early as the 3rd century. Often vastly disproportionate in scale, ancient maps instead highlight important features of the city at any given moment. Nanjing’s magnificent city walls for example consistently feature prominently in maps of the last 600 years.

- When Art History Goes into the Washing Machine

- Five Steps to Fudging with Finesse

- Making a Mark; The Power of Peppa

When Nanjing became capital again in 1927, there was a great frenzy of map making, as the government drew up blueprints of a city that was to be an exemplar of modern China. Maps were made to demark districts, to carve out the transport and sewage systems, but in reality few of them reflected the true state of the city at the time; predominantly open fields with a number of overflowing shantytowns. These maps were idealised visions of a Nanjing to be. They were not made to navigate through the city, but to navigate through Nanjing’s, and indeed China’s, “glorious rejuvenation”.

It’s easy to think that with satellite imaging, maps these days lack the complexity of hidden meanings found in their earlier editions, laden with inaccuracies and distortions, but just as maps become evermore sophisticated, so they are embellished with more intricate layers of meaning that have plenty to say about when, where and who is sat at the drawing board.