Those who are fans of Miss Universe may be familiar with a certain comedian/host named Steve Harvey who famously, and incorrectly, blurted out Miss Colombia as winner of the 2016 competition. Quickly afterwards he corrected himself, which was followed by an awkward re-crowning of Miss Philippines as the actual winner.

This same comedian, on his eponymous show, made another faux pas by directly commenting about the attractiveness of Asian Men. During this episode, Steve Harvey presented the cover of a book called “How to Date a White Woman: A Practical Guide for Asian Men”. He then immediately asked and answered for the live audience, “Excuse me, do you like Asian men? No, thank you”. He then continued, “You like Asian men? I don’t even like Chinese food. It don’t stay with you no time. I don’t eat what I can’t pronounce”.

While anti-Chinese/anti-Asian movements have died down considerably since their height in the 1800s, comments continue to colour relations between Asian and European Americans, both on an individual and group level. Depending on location in the U.S., there can be a high level of representation and integration of Chinese culture and language; bilingual Mandarin language schools, historic Chinatowns, authentic vs. American style Chinese restaurants, plus the prevalence of Pearl Tea. Despite an increase in both political and cultural awareness, conflicts continue to take various forms between European and Chinese-American cultural groups.

~ The 19th century ~

The Chinese, as an American ethnic minority group, only started to be fully recognised in the early and mid 19th century. In 1830, the United States issued its first census that listed only three Chinese citizens. In the 1860s and 70s, working men of Caucasian or European background began to form an anti-Chinese movement within political groups and employee unions. States were quick to restrict the number of incoming Chinese workers and highly encouraged those in situ to consider returning to China.

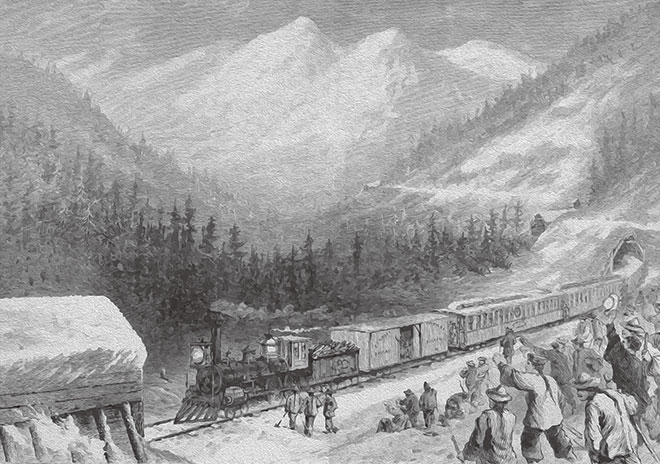

In 1863, Charles Crocker, founder of the Central Pacific Railroad, hired fifty Chinese workers from various backgrounds; miners, laundry attendants, labourers, domestic servants and gardeners. Crocker was very happy with the results, commenting that the Chinese were, “quiet, peaceable, patient, industrious and economical”. Sentiments such as this contributed to the mounting resentment against the hard working Chinese who worked for pitiful wages. As Chinese immigrants became one of the largest workforces on the railroads, a project that would change the American landscape forever, the anti-Chinese movement worked to end Chinese immigration completely, both through political persuasion and physical violence, to person and property.

That for ways that are dark

And for tricks that are vain,

The heathen Chinee is peculiar, —

Which the same I am free to maintain.

[“The Heathen Chinee”, originally “Plain Language from Truthful James”, by U.S. writer Bret Harte (1870)]

A newspaper writer from the state of Washington wrote similarly blunt thoughts and raised insulting questions about Chinese and Chinese-Americans participating in the American workforce; “Why permit an army of leprous, prosperitysucking, progressblasting Asiatics befoul our thoroughfares, degrade the city, repel immigration, drive out our people, break up our homes, take employment from our countrymen, [and] corrupt the morals of our youth?”

Yet despite such rabid hate and vitriol directed towards Chinese immigrants and their steadily growing presence, well-known social reformer and writer Frederick Douglass was strongly opposed to the anti-Chinese campaign; “I want a home here not only for the negro, the mulatto and the Latin races; but I want the Asiatic to find a home here in the United States, and feel at home here, both for his sake and for ours.” It would be sentiments such as Frederick Douglas’ as well as the growing national identity of the melting pot that would change the nature of communication and conflict between Chinese and European-Americans.

~ 19th/20th century ~

The 20th century saw further integration of Chinese groups into American society through developing Chinatowns and growing local families. However, the community continued to struggle, as reflected through isolated events and underlying trends. In 1909, the murder of Elsie Sigel in New York resulted in the unfair scapegoating of a Chinese person and an increase in the harassment of Chinese individuals and communities across the United States as well as a surge in the portrayal of Chinese men as “horrible, dangerous monsters” to “innocent, moral” white women.

This era also saw the rise of the phrase “yellow peril” in newspapers owned by the then media mogul William Randolph Hearst. William F. Wu, author of the 1982 book, “The Yellow Peril: Chinese Americans in American Fiction” (1940), wrote about how Chinese characters were somewhat based on the popular Fu Manchu, a British-created symbol of the evil mastermind, with traditional clothes from the Qing dynasty, a hair cue, impressively long nails and a long mustache hanging from both sides of his upper lip. Most of these characters were written as individuals of Chinese descent, yet it is interesting to note that the number of Japanese characters increased as Japan began to rise as a geopolitical threat.

Xenophobia in the media was picked up by the public and quickly followed by the implementation of the Page Act of 1875, which prohibited “undesirable” immigrants from entering the country. “Undesirable” described individuals from Asia who were entering the U.S. to become labourers plus individuals who were convicts in their home country, among others. Other acts, such as the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act and the Immigration Act of 1917, barred Asians in a time were nativism was the norm. As World War II progressed, Japanese-Americans became the new “force of evil” following the attack on Pearl Harbour, which also led to the internment of Japanese and Japanese-Americans by President Franklin D. Roosevelt. Only with the passage of the 1965 Immigration and Nationality act were immigration quotas based on nationality abolished, resulting in an influx of Asian immigrants to the American mainland.

~ Present 21st century ~

Current anti-Chinese sentiment in America is thought to stem from the perception of China’s rise on the international stage as a crucial geopolitical player. Austin, Texas-based Global Language Monitor, that analyses trends in language usage worldwide, identified China’s rise to power as the top news topic of the 21st century in electronic media and international print sources. During the 2010 U.S. midterm elections, a significant number of advertisements negatively focused on an individual candidate’s alleged support for free trade with China.

Despite Chinese culture proliferating throughout the United States via media, politics, culture and art, a number of misunderstandings and insults remain part of the Asian-American experience. Fox News, a well-known conservative news outlet, aired a segment called “Watters’ World” on the “O’Reilly Factor”, a political commentary show hosted by presently embattled Bill O’Reilly, where correspondent Jesse Watters visited New York City’s Chinatown to interview Chinese-American voters about the 2016 elections and candidates. The segment depicted biased stereotypes and denigrated Chinatown residents who could not speak English. Watters also made some culturally insensitive jokes pertaining to vendors selling stolen property and asked insensitive questions about China “taking care of” North Korea, their karate skills (actually a Japanese martial art), and “performance enhancing” herbs. The segment was sprinkled with clips from the Karate Kid and other films that were meant to demean the answers of the interviewees. While Fox News has often been historically insensitive towards minority groups in its coverage of socio-political trends, the segment was seen as especially insulting of Chinese immigrants and Chinese-Americans during a particularly sensitive time in American politics. Another example of a local conflict that mirrored a national experience was when Michael Luo, a New York Times reporter, was surprised by an angry stranger who told him to “go back to China”. Michael Luo subsequently turned his experience into a platform for other Asian-Americans to speak out about personal instances that may have been fueled by or coloured with racist undertones.

Luo first wrote an essay, addressed to the original aggressor, describing his and his family’s feelings as they were walking from Church to lunch; “Maybe you don’t know this, but the insults you hurled at my family get to the heart of the Asian-American experience. It’s this persistent sense of otherness that a lot of us struggle with every day”. The American-born reporter has seen an abundance of support, especially on twitter after Luo invited Asian Americans to “…tweet…your own racist encounters” with the hashtag #thisis2016. With everything from being called “intimidating” for an Asian woman to being asked when their work visa ended to teachers asking if their name was Ching Chang Wang, these insults do not just hurt the individual but also reflect a larger social intolerance that has affected Asian Americans for over 2 centuries.

While there are similarities between and overall trends to the Chinese and European-American relationship, experiences vary across the country. In the San Francisco Bay Area, there is an abundance of opportunity, both for new immigrants and local residents, to experience cultures from far lands.

Kai-Yao To, Taiwan native, teacher, and Bay Area resident for over 25 years, has seen tremendous change in the social and political landscape of the U.S. Despite living in one of the most liberal and international parts of the country, speaking with The Nanjinger, Kai commented, “There is always something happening in terms of social unrest; racism continues to be a problem in this country. I have experienced it a few times. But I can speak and stand up for myself, which has made the negative experiences easier to deal with. Usually, when others target me it’s because they think I don’t speak English or because I am afraid to talk back”.

Kai’s outspokenness and has not only led to personal success as an American citizen, but also professionally as a business owner, manager and teacher; “I’m very confident and can deal with problems as they arise. I don’t feel that being Asian influences my chances to be successful in the United States, and I don’t feel that I have been treated as less.”

Lan Miao, a Southern California native who has lived in both the U.S. and Taiwan, has had various experiences as an expatriate and an American-born minority. As a librarian and educator at a bilingual mandarin school in Berkeley, Lan uses her bicultural and bilingual background to assist Chinese and English language teachers by supplying them modern educational language materials. Her success as an educator has helped the school flourish as a landmark bilingual IB school in the East Bay. However, she has a more sober idea about being successful as a Chinese woman, commenting, “In high school, I took a college level art class with a teacher who was really encouraging and liked my art. My teacher happened to be an African-American woman and she told me that if I want to pursue art as a profession, I would need a master degree because I’m a woman and a minority. It was hard for me to believe her. I thought this was a problem for her generation in the 80s; but now, I totally get what she said”.

As the US continues to grow as a multinational and multicultural nation, future generations of Chinese and Asian Americans might face similar, if not evolving, issues in terms of facing social and political aggression. Lan added, “I think Chinese Americans are going to face challenges for a while, especially depending on where they are in the U.S. Just in this country alone you have different paces for modernisation. And for a lot of people it’s not the norm. It’s kind of infuriating to see how some European Americans feel and are treated as if they have the privilege being more American than Asian-Americans. I don’t think it’s completely hopeless, but I think it will take a few more generations for us to reach equality”.

Kai expresses a similarly cautious sentiment for the future and advises future immigrants to take a stand for themselves; “No matter how people are treating you; you need to know how to speak up for yourself. Within our current political climate, things may worsen, but it really depends on your location within the country”.

As we all become more interconnected through media, business, politics and cultural exchange, our understanding of individual and community continues to diversify and become more complex. Being a country of immigrants, the U.S. continues to question its identity and there will be more opportunities to identify differences and similarities between Chinese and European Americans. We may happily dole out our dollars for pearl tea and fried rice, yet we also need understand more about how we can all be involved in living up to our name as a melting pot.