Upon the relics of our ancestors, we strew technology and investment in the name of reinvigoration. Then, on those formerly dusty sites, we gladly bestow the brand-new architecture with blossoming light bulbs and vining glass ornaments.

Such is how Nanjing’s new cultural landmarks have been created in the last decade. They are hybrids of history and modernity. Standing in the Porcelain Tower Relic Park, I was aware of this change that seems subtle but has nevertheless suffused corners of the city with which I am so familiar.

If time rewinds to the years when “cultural attractions” still meant “keeping our historical relics just as they are”, I would have described Nanjing’s attractions as quiet, old-fashioned places we visit simply for the sake of paying tribute. Standing obstinately with their dim walls and solemn atmosphere, they are frozen tokens of the past; skeletons of the old Nanjing alive only in history books and grandparents’ tales. The space locked up within those imposing red walls, city walls and marble walls was always immense, but there was no way I, a modern-era child in today’s clothing, could blend in without being a pebble dropped into an undisturbed pond.

There was no way these settings and I could become one with the inevitable gap of time and style wedged between.

So I inquired as to their secrets with silent gaze.

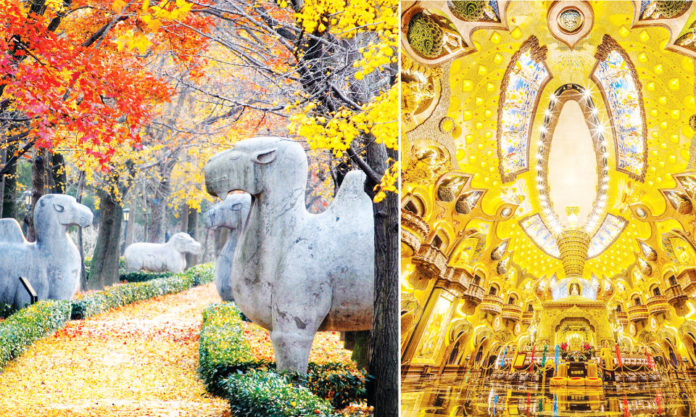

When modern technology found its place in Nanjing’s newly emerging cultural attractions, the first splashes were indeed breathtaking. In 2014, the Six Dynasties Museum, masterpiece of Mr. Bei Jianzhong, joined the cultural block of Changjiang Lu. In 2015, Niushou Shan’s Usnisa Palace, with its lavishly embellished dome and marble corridors that wore the lustre of ¥4 billion, made a stunning debut. In the same year, the construction of the Porcelain Tower Relic Park was completed, and the tower that was once one of Seven Wonders of the Middle Ages was reborn as a tower of glass. All three projects took place upon Nanjing’s important relics, and all three aimed to reinvigorate those relics with a more modern intelligence.

Interestingly, as a native Nanjinger, I came to know about those newly-emerging landmarks, not through dinner-time chats with my elder family members (like I used to when they gave me advice on which fun parts of Nanjing to explore after school), but through social media.

These were photos of girls posing against the Porcelain Tower’s brilliant LED background, hands spreading their Hanfu dress, and close-ups of the interior of the Six Dynasties Museum, featuring silhouettes of bamboo on linen curtains and plastic plum blossom branches curling with deliberate quaintness. Plainly suggestive of the designers’ ambition to combine archaic Chinese style with modern aesthetic, to some degree, the attempt worked well.

Contrary to the attractions developed decades earlier, where mossy bricks are the modest objects of inquiry, Nanjing’s new generation of cultural landmarks comprise shiny glass showcases, newly-painted murals and sophisticated lighting effects. While all eager to radiate their glamour and absorb visitors, patrons to such are very often youngsters estranged to the city’s history.

The older cultural attractions are sanctuaries of the undisturbed past, while the newest ones are galleries opened up toward modernity.

Thus, while the Ming Xiaoling Mausoleum, City Wall gates and Confucius Temple remain the distinct landmarks of Nanjing in the minds of the elder, so the reputations of the Six Dynasties Museum, Usnisa Palace and the Porcelain Tower Relic Park grow with the aid of the fast-developing internet. The latter seem to fit better into the vibe of modern Nanjing.

So do Nanjing’s newer cultural attractions have a definite advantage over the older ones?

I saw the answer, “no”, in the Porcelain Tower Relic Park. The brightly-lit walls with hanging lights and the embossed and polished sculptures of characters from Buddhist stories were remarkable, though not as remarkable as they appear online in photos with filters turned on, but there was something that confused me throughout the whole tour. Walking through the souvenir stores, I finally understood that puzzlement. Were the archaised sights that would each fit perfectly into photo frames what I came for? Did I see what I ought to see?

The root of the confusion, I believe, is that the focus of the exhibition drifts from its initial purpose. The park, just as its name suggests, was constructed to better introduce the rich story behind the Porcelain Tower to the public, but when the actual relic of the tower is endowed with a modern design, it loses its power to provoke visitors’ inquiry. When the space is bustling with hints of the modern world, there is not much silence left for one to quietly ponder a piece of coloured glaze from 6 centuries ago; to realise she remains estranged from her city’s complicated past.

The same applies to the Six Dynasties Museum and the Usnisa Palace. We feast our eyes on their splendid, innovative design, but at the same time, we forget to give due significance to the relics upon which they stand. The emphasis of such cultural attractions now falls on “attraction” rather than “cultural”.

In many ways, Nanjing’s new cultural attractions bring things together; they demonstrate how technology and modern aesthetics can connect a young generation to historical relics. On the other hand, however, they eliminate the space for our contemplation of the relics and their past. That brought together is worthy of applause, but that which is broken apart needs to be fixed in time.