The selection of books regarding China in any given library is, generally speaking, diametric in nature. The opinions expressed by authors range from those predicting China will surpass the United States and be crowned the sole world power to those suggesting that its collapse is imminent. In many respects, to a casual, objective observer of the information produced in the West regarding China, it appears to be more focused on alleviating one’s personal fears about the country or pandering to prejudices; if one thinks America, for example, is being poorly run, read books commending the Chinese economic surge; if one views China as a threat, read about its recklessness; its certain decline. Perhaps Wade Shepard’s recent book, Ghost Cities of China, is attempting to make its bed with a third group of readers looking for a more level account of the country that has transformed from nearly universal poverty to economic might within roughly the same time that Kansas City, my home, proposed a light rail system, voted in favour of it, and then essentially proceeded to not build it.

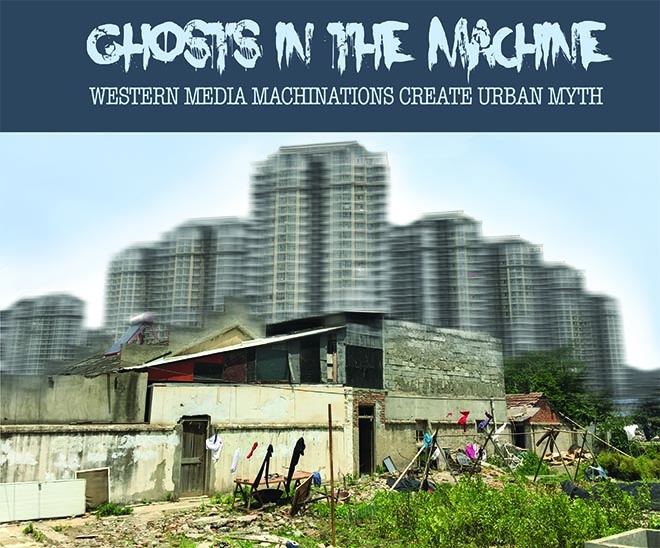

The book is very concerned with analysing and providing a touch of humanity to the largely unpopulated “ghost cities” that have popped up around China, captivating the world’s attention. Its attempts to debunk the popular Western narrative of these ghost cities have a modern, rogue-journalist feel.

For example, Shepard describes how he went to the city of Zhengdong, declared a “ghost city” by the popular American television program 60 Minutes, only a few days after their report had aired, “loaded up the 60 Minutes story on [his] laptop and invited the waitresses over to watch.”

This anecdote from the book ended with the waitresses’ surprise at the report’s claim that there were no people in Zhengdong for “miles and miles,” as it did not meet the reality of their lives; roughly 2.5 million people were living there at the time, more than the total population of Houston, Texas in just one Chinese city.

In addition to the portraits drawn up of his own endeavours to get to the reality of the “ghost cities” story, Shepard also touches on the grit of the issue at hand. He explains the policies behind the funding of these massive development projects and their expectations as well. He points out successes and failures and makes predictions for the future.

In the end, the book left me with the feeling that what makes the whole situation truly interesting is not its recklessness, but rather its unabashed rationality.

Today in China, economic models are being implemented religiously in the interest of rapidly urbanising the country. Subways, eco-friendly developments and the construction of virtually brand new cities are included in this drive that sometimes appears more like a well-thought-out game of Sim City than the management of a country itself. Furthermore, unlike the West, the Chinese do not seem concerned by this. The book posits, rather, that it is often seen as a necessary stepping-stone to the country’s future.

In stark contrast to this national situation, I found the book to be both succinct and clear. With a mixture of personal anecdotes and analysis of outside research on the topic, Wade Shepard weaves together his take on the ghost cities of China. It felt balanced, neither proclaiming the situation’s brilliance nor its insanity. Instead, the reader is left with a wealth of material to argue in support of either extreme. This is not an academic work per se, but it does provide a good read for someone looking for a fair introduction to the Chinese phenomenon dubbed “ghost cities.”

After finishing the book, I had the chance to sit down with Wade Shepard and talk about his work. At ten o’clock on a Saturday morning, Shepard was dressed smartly, sporting a long-sleeve suit jacket that nearly succeeded in concealing the wealth of tattoos that crept down his arms, but not quite. At his suggestion, we each ordered a pint. Below, I’ve included some of the highlights from our interview.

Q: Your book pointed out the 60 Minutes story regarding Zhengdong. Would you say they sacrificed good journalism in order to create a viral story?

“When the 60 Minutes report aired I was actually in Zhengdong New District, along with over a million other people. What was funny about the 60 Minutes ghost cities report was that within Zhengdong there are some developments that are so new that they are very much uninhabited, but they didn’t film there. Instead they went right into the central business district, a place that is the banking capital of Henan province and has the regional headquarters of HSBC and all of China’s big banks among its 150 financial institutions. What they said was empty for “miles and miles and miles and miles” was actually a place that was packed full of cars and people, corporate offices and businesses. I actually went to the same places and tried to get the same videos, but couldn’t. There were just too many cars and too many people.

“We should talk about what good journalism is. In for-profit media, good journalism is what gets a captive audience. They love the idea of this crazy place on the other side of the world that does things we can’t understand. It goes with the mentality that China is building their own doom. I don’t want to say they lied. I just want to say they went to China with a pre-written script they were bent on fulfilling by any means necessary.”

Q: A housing bubble largely fueled the 2008 financial crisis, but your book argues that a similar situation could not happen in China. How do you justify this statement?

“People in the USA were paying for this property with money they took out in loans, so when the property market started going down it caused an economic domino effect. It took many businesses down with it all the way up the chain. In China you won’t see this happen because people are buying lots of property with cash. They use cash and they use it to save their money. In order for a bubble to pop, you need a mass selloff. In China, there is no incentive for a massive selloff, because what are people going to do, sell the house and keep money in the bank? Store it in stocks or bonds? No. They’re buying houses because they have nothing else to do with their money.

“Recent measures have had a negative impact on China’s housing market. Previously, housing in China was very opaque money laundering and stashing of illicitly received funds. With Xi’s crackdown, this major driver of real estate sales virtually disappeared overnight, but even this won’t cause the bubble to burst, if there ever was one.”

Q: Your book describes Chinese architecture as being at a point of adolescence. How do you see it developing?

“Well, communism essentially wiped the architectural slate clean. Everything was very pragmatic, but that’s not appealing right now. So afterwards it leads to this kind of artistic search. They are just trying new styles because they can. I think China is in this crazy kind of adolescent phase; you dress kind of funny, trying to wear new clothes and find your own style. Overall it’s just like Chinese mass culture. It’s a culture that’s still searching, trying to find its own footing, and its no better manifested than in it’s architecture.”

My interview with Wade Shepard left a great deal to be digested. From his contention that media outlets on which the West depends are unreliable, to his anecdote-driven arguments as to why we should not sensationalize our reporting of China (e.g. through footage of “ghost cities”, filmed during Chinese New Year), my interview with Shepard, along with his book, was not merely about ghost cities in China. It also got at the deeper questions regarding the ways in which we should report on China, not to mention the future of this ever-fluctuating country, as well.

Towards the end of our interview, Shepard and I discussed the differences between ghost cities in the United States and those in China. As he explained in his book, the abandoned towns found in the rust belts of America are victims of a changing economy. Walking through them, one may wonder, “what happened here?” But in China this is not the case.

Walking through the empty ghost cities of China, the compelling question is “What will happen here?”

Posing this question to Shepard obviously elicited an avalanche of theories, from the idea that the current buildings are temporary and will be rebuilt later, to the reality that our understanding of China is limited because it is doing things that have never been done before. Eventually he arrived at his conclusion and, in a moment of genuine honesty, proclaimed; “So basically what I’m saying is I have no idea.”

Just as a college professor explained to me how he was taught in 1990 that the Soviet Union would last for at least another fifty years; we just don’t know. That said, the one thing Ghost Cities of China truly impressed upon me is the notion that these uninhabited cities are part of a coherent plan, and will probably be populated and functioning normally long before any light rail trains become a viable means of mass transportation in Kansas City.

This article was first published in The Nanjinger Magazine, June 2015 Issue. If you would like to read the whole magazine, please follow this link.