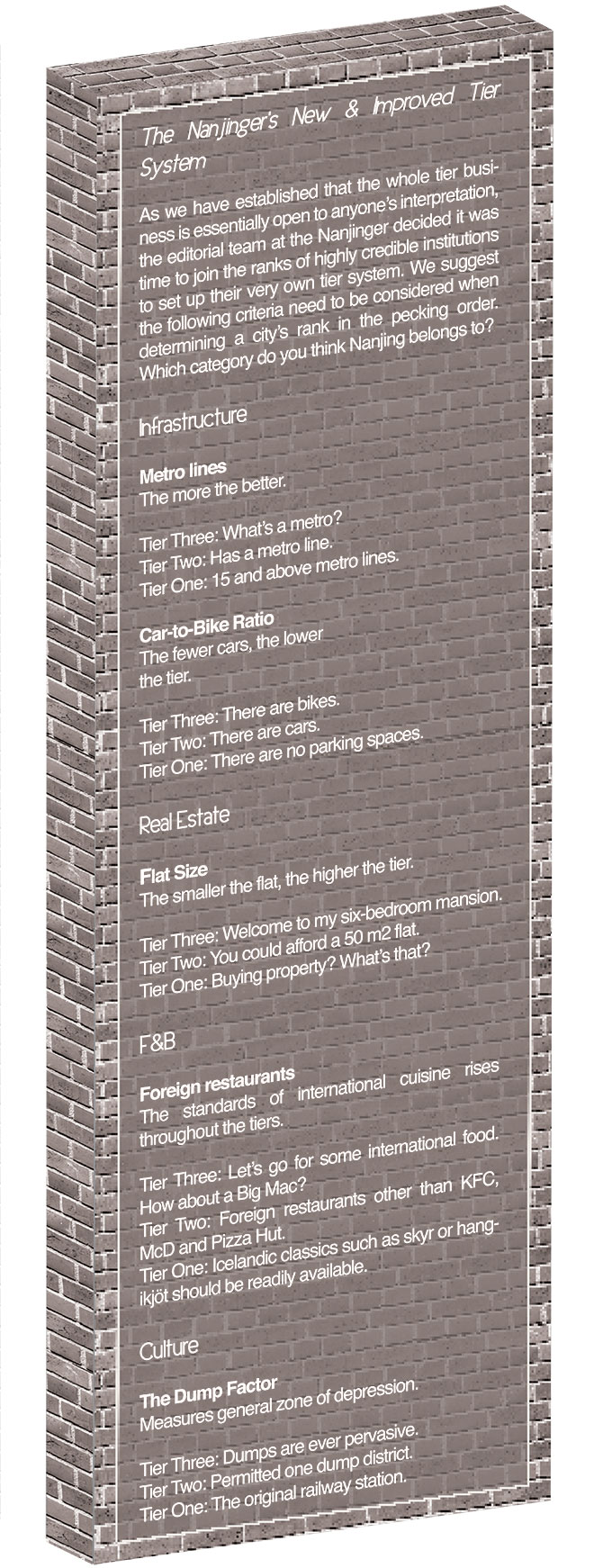

“We often hear of China’s first or second or third tier cities, yet what actually makes a city tier? The terms are so often used, yet there is no official formula for determining what tier a city falls in. Instead, everyone makes up their own rules.”

chinasourcingblog.org, July 2011

China’s urbanisation story is without doubt a fascinating tale. Throughout the last three decades, the Middle Kingdom has not only exhibited the fastest urbanisation rate in the world, but its pace of development is simply astonishing. In 1978, the beginning of what was to become China’s grand Opening-Up and Reform era, over 82 percent of Chinese people lived in rural areas. 35 years later 53 percent of the population have moved to the cities, and it does not end there. The government’s ambitious plan is to drive the rate up to 60 percent by the time we welcome the new decade.

With such an incredible track record and China’s developmentally varied urban landscape, it seems there was a need for a system of categorisation to make sure the general populous could wrap their head around which cities are great places to be born and which are “still in the works”. This ranking system is commonly known as “tier”.

A city’s tier determines its rank in the urban pecking order, another matter of face that makes the higher-tier ranks something to aspire to. Only four cities in China have for a majority of the time held the sought-after “first tier” denomination; Shanghai, Beijing, Guangzhou and Shenzhen. Last year, Tianjin joined the club. It seems common knowledge which are China’s leading cities, just as everyone is aware of their own city’s tier as a method of validation. Countless small talk scenarios include the following conversation: “So, where are you from?” “[Insert city here].” “Oh, what tier is that?” “[Insert tier plus proud face for first and second, embarrassed face for three and below].”

Tier One or Two – Says Who?

Yet, here’s the kicker. This system of validation that gives certain cities so much power over others is truly just common knowledge; nothing else. In fact, there is a lot of confusion with regards to Tianjin and Chongqing’s first tier city status in particular; are they or aren’t they? That is the question.

There are two reasons such confusion could arise. For one, the system has never been officially recognized by the Chinese authorities. Secondly, too many cooks have indeed spoiled the broth. Not only does this information remain unpublished by any government body, it is instead released by many different parties such as, on the local side, CBNweekly, a business news magazine founded by Shanghai Media Group and produced by China Business Network Media (CBN). On an international level, Forbes, market research mogul Nielsen and real estate company Jones Lang LaSalle have also jumped in on the tier race, publishing their own interpretation of the rankings.

The whole tiering process is further confused by the fact that each of the parties might use slightly differing criteria for their measurements, leading to varying results.

If that were not muddled enough, no longer satisfied with the simple gold, silver, bronze ranking system, many organisations have now taken to adding layers of further classification to the list; once again these can differ according to the publishing party. So it happens that some rankings talk of strong, middle and weak second tier cities, as the gap between leading Tier 2 cities (in which Nanjing is generally included) and those on the lower end of the scale such as Hefei or Nanchang is so large it would constitute an insult to the former to be seen as developmentally identical to the latter.

Another way of expressing the strides that certain cities such as Nanjing or Chongqing have made is to refer to them as 1.5 tier cities, as was done by the aforementioned JLL in their China60 report, compiled from data gathered between 2006 and 2015. This ranking is one example of how radically different the results can look, depending on one’s approach.

China60 looked at China’s leading cities from an economic and property market perspective and came to a very different conclusion than CBNweekly. The report sees Beijing and Shanghai as “über-cities”, the tierless leaders of the nation, who are so far ahead of any other city, they are above being ranked. On Tier 1 we find just two contenders, unsurprisingly Guangzhou and Shenzhen. The Chinese abbreviation 굇밤 often lumps these cities together as “the big four” (ever noticed how China loves grouping things in fours?). Suggesting that Beijing and Shanghai remain an unattainable category of their own, hence excluding them from any ranking, was the first step in drawing the Chinese public’s ire.

No sign of Tianjin in the first tier section either, contrary to CBNweekly’s promotion of the coastal hub to China’s upper class. Instead, the Special Administration Zone and neighbour to the capital finds itself in the 1.5 category aside a bunch of the usual suspects such as Hangzhou or Chengdu. While the ranking has drawn much criticism from mainlanders, who seem to be grappling with the 1.5 tier concept, JLL is a big name in the industry and has almost a decade of collecting data to which it can look for its research. For Jiangsu, this study is great news as nine of the cities of the province, whose GDP output was only bested by Guangdong in 2014, have made it onto JLL’s Top 60 list.

The Criteria behind the Tier

As the results of the tiering vary, so do the methods.

Online property trading website RightSite.com provided an insight into the influencing factors of tiers as early as 2009. They included: Population of more than five million people Provincial GDP of at least ¥250 billion, or ¥350 billion in more prosperous provinces Cities with strong economic growth Geography, i.e. cities which are the most significant in their area (such as Xiamen, though population is less than 5 million), Advanced transportation infrastructure Historical and cultural significance (such as Guilin, a tourist hub despite its small size)

JLL’s ranking adds much more complexity and has very different points of focus, spanning GDP, population, wealth, investment, retail sales, household savings, educational infrastructure, the amount of land, the number of retailers and other variables.

Just these two examples show how fundamentally different the approach to tiering can be. No wonder most of us have no clue whether Tianjin is Tier 1, 1.5 or 2 this week, and even less what it will be next.

In light of all this chaos and confusion, some companies are even attempting to move entirely away from a tier-based classification of China’s urban environment. In 2009, consulting firm McKinsey released a study that introduced the concept of city clusters as an alternative to tiers. One cluster constitues groups of cities that are developing around one or two large cities. McKinsey identified 22 clusters nationwide, and further divided them into subcategories of mega, large and small.

Yet, over half a decade late, the tiers are still taking their toll. Their hold on society is as strong as ever.

No One Sheds a Tier

The irony is undeniable. While the tier system can be called sketchy at best, China’s cities have long since seen the effects of a tier stamp being slapped onto their faces with very realistic ramifications.

In terms of the country’s elite cities, they continue to cannibalise all that sit below them. The “BSGS” quadruple threat attracts the country’s brightest graduates from home and overseas. Their status as mega-cities has resulted in a lower-tier brain drain that sees the less aspirational or the more filial children stay behind in the lot into which they were born. While the rural-to-urban migration and its devastating effects are well known, the tier-trade-up effect is not perceived as quite as harrowing. Nevertheless, many local governments of second and lower tier cities offer attractive business loans and support to young graduates and would-be entrepreneurs, no doubt in an attempt to attract local talent and keep them from abandoning their place of origin for their more tiered-up rivals.

From an international investment perspective, the tier system has also had a concerning effect. Foreign companies have traditionally looked to what China60 called the Alpha Cities, i.e. Beijing and Shanghai, when it came to entering the local market. It has taken years for them to realise that China has profitable markets to offer beyond the Top 2. The good news for Nanjingers in particular is that this limited tunnel-vision type approach is on its way out. While Beijing and Shanghai remain the first stop to test local waters for new businesses, an increasing amount of attention is being directed to the developing middle class consumers in second tier cities, whose markets are not as oversaturated as the Alphas. It was just a question of time before those two got fat and lazy and the younger, more dynamic cities got their turn.

Such is the motivating factor behind reports such as China60 or the PwC report, “Chinese Cities of Opportunity” in conjunction with the China Development Research Foundation. The latter looks at 15 Chinese cities and their development potential, presenting a strong case for marketing managers to cast their eye to the previously internationally neglected second tiers.

As Wolfgang Hirn for the German economic news outlet Manager Magazin proclaims quite rightly;

“In Beijing, in Shanghai – that is where you need to be. This was the mantra of market entry consultants for a long time. However, those days are over. A presence in these two metropoli (and possibly Guangzhou down South) is not enough anymore to distribute your goods among the Chinese populace.”

Instead, eyes are now turning to the previous silver medalists; Shenzhen, Guangzhou and in third place our very own Nanjing, “newcomers” who are on the forefront of the new urban rush of international companies. Nanjing does very well in PwC’s ranking, leading the nation’s intellectual capital and innovation sector and in the category demographics and livability. One cannot deny the winds are a-changing as it is hip to be Tier 2. While we won’t be saying good-bye to the elitist city hierarchy anytime soon, despite its very questionable claim to legitimacy, at least Nanjing can look forward to some more investor attention in the near future.

This article was first published in The Nanjinger Magazine, June 2015 Issue. If you would like to read the whole magazine, please follow this link.