Nanjing’s long-standing food vendors and eateries in downtown neighbourhoods offer a real taste of city and local life. I go back to those places when I can, preferably later in the afternoon to bring something home for a simple supper, and, like many other Nanjingers (or the older ones perhaps), I always get a bag of “shaobing” (烧饼). You must try them if you haven’t, but it is even better to appreciate these humble pastries in some cultural context.

“Bing” apart from being a search engine which you’d use only when you don’t have a VPN, is a major category in the diverse world of Chinese wheat foods. Simply put, it’s anything that is flat and rounded, whether steamed, fried, or baked, leavened or unleavened, with or without fillings, round or oval, gigantic or petite.

But we’re talking about a specific type of bing; the shaobing, which means “baked bing” in classical Chinese. Whereas almost all wheat foods in China were boiled or steamed, as suggested by archaeological findings, it was perhaps not until the 2nd century CE that travellers from the Middle East or Central Asia introduced “baked bings” to the Chinese, presumably sharing the same origin with naan and pita bread. In fact, many shaobing bakeries today still bake in tandoor-like ovens.

These baked, exotic bings soon became popular in China and, along with some major migrations in Chinese history, were brought to almost every corner of the large empire in the following millennium. The shaobing made in different areas continued to develop into numerous variations in the hands of local bakers. In Jiangsu province alone, you can easily find at least a dozen major variations. This makes it impossible to translate “shaobing” into a single English term; it may be “flat bread” in this city and “pie” in another.

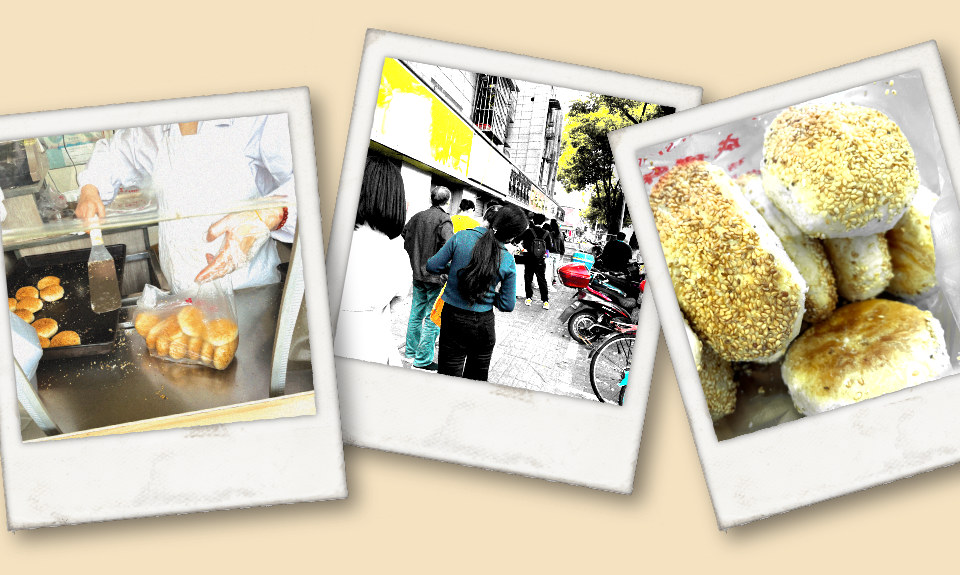

In Nanjing, shaobings are a favourite companion with mini wontons or duck-blood noodle soup, and they are often made with, unsurprisingly, duck-fat shortening. They first appeared in Chinese Muslim (Hui) restaurants and delicatessens which have been popular in Nanjing for centuries. Using the by-product of Nanjing’s favourite bird, these shaobings started as a halal substitute for the lard-laminated ones made in other parts of Jiangsu and Anhui. But over time, they have evolved into a distinctive regional type that eventually defines shaobing in the Nanjingers’ lexicon. They are about the size of a palm, with dozens of paper-thin layers that are crunchy and soft at the same time. They come with two shapes and two fillings; the oval-shaped are savoury, flavoured with minced scallions and softened fat at the centre, while the round-shaped are sweet, using a fine layer of sugar crystals (and often with ground black sesame) instead. Both are generously covered with white sesame seeds on the top.

Which store makes the best shaobing in Nanjing? That question is of little interest to locals, just like New Yorkers do not travel across the city to find the best bagel shop; they just buy them downstairs. They are too commonplace. It was not until recent years, with the rise of social media and review websites, that some better shaobing bakeries became renowned beyond their communities. Among all the delicious shaobing bakeries in the city, Chengcheng (成诚酥烧饼) has always been my favorite since 2009 when I moved to the neighbourhood and discovered this hidden gem. Setting the competition of “the best” aside, there should be no doubt that Chengcheng at least makes the flakiest shaobing in town. To me, the flakiest means the best. You will love them if you are, like me, a fan of mille-feuille, baklava and croissant. Be aware, however, if you only look for halal food. Even local people would often assume Chengcheng use duck fat like many other places. Indeed, they look and taste very similar to the duck-fat ones, but they use lard.

The owners of Chengcheng started their business in the city centre before they moved to the current location about 20 years ago. Located at 127 Shuiximen Da Jie, steps away from the south gate of the Mochou Lake Park, this small bakery is well situated in the Nanhu area; one of Nanjing’s largest neighbourhood built in the 80s and renowned for some of the busiest markets, eateries and delicatessens around.

Chengcheng offers four types of filling for you to choose from; salted scallion (葱油; ¥1.4 each), sweetened black sesame (脂麻; ¥1.4 each), sweetened red bean paste, (豆沙; ¥2.2 each) and ground pork (肉; ¥4 each). All of them are regarded by most as shaobing. Technically speaking, however, only the first two are shaobing, whereas the latter are “mooncakes.” The terminological difference is spelled out on their menu board, and I like that precision.

Each of the four fillings has its own loyal fans, and I would recommend anyone to try all. Suppose, however, that Chengcheng decide to keep only one option and stop making the rest three, I would hope they keep the scallion one.

As mentioned earlier, standing in the queue is almost inevitable before getting your baked goodies, but that should take no more than 10 minutes. In fact, it is always an enjoyable experience for me as I watch other customers come, order and leave. Those who jump back and forth to read the menu board are usually first-time buyers from other parts of the city who found this place by recommendation. Those who ask directly for “the scallion” or “the sesame” without the help of the board are often the younger or newer frequenters. Older people who have been living in this area for decades do not use words like that. They use “the savory” (scallion) or “the sweet” (black sesame) instead. This may seem confusing because there are other savory and sweet options, but the staff here never fail to understand the jargon.

Once it is your turn, order perhaps thirteen pieces of the scallion, eight of the sesame, five of the red bean, and nine of the meat. While the QR code that you scanned for payment is still loading, the lady by the shop window would have already collected each of the flavours from different baking trays in their correct numbers, by which time she would have also told you that the sum is ¥76.4, all done with amazing speed and accuracy. I appreciate her professionalism so much that I never mind how fierce she sometimes looks and sounds.

An exceptional advantage of buying from a busy bakery like Chengcheng is that you always get your pastries fresh and warm, as they bake while they sell. Sometimes they sell out a batch so quickly that people have to wait for the next batch to come from the oven, but who would mind that?

One of my best memories is walking back home at sunset while eating shaobing from Chengcheng’s plastic bag. But beware that the crispy layers tend to break into small pieces and fall off everywhere like snowflakes along with the sesame seeds. Think twice if you are on your first date.

Originally known as an exotic bread from Central Asia, shaobing has long become one of the most loved foods all over China and a representation of various regional flavours. To me, a piece of scallion shaobing with a bowl of wonton soup is all I need for a nostalgic taste of home and an eternal source of comfort and happiness.