“When I Find Myself in Times of Trouble…”

September is always a funny month for me. The daylight begins to contract, school imposes routine on the wildness of the summer months, and for the last 27 years, the anniversary of the death of my mother. 7 September used to be my Grandmother’s wedding anniversary, and then, one day in 1994, it became a different anniversary, one that has shaded life ever since. Life, love, grief and death. The ingredients of every great story.

Joan Didion writes about this in her tour de force memoir, “The Year of Magical Thinking”. In clear, crisp prose she dissects the grieving process, meandering through the stages of grief that span 1 year and 1 day exactly from the sudden death of her husband, John Gregory Dunne. It is an honest recount, flitting from mundane to magical moments, when grief baffled and bemused and battered her. Early on, she writes of how the need to keep her husband’s shoes made sense in those addled days. She kept them, because he would need them when he came back.

Of course. Like not walking under a ladder, or knocking on wood, like wearing your lucky underwear or throwing a pinch of spilled salt over your left shoulder; some things make sense in the liminal spaces, and that is enough. Enough to create a stepping stone to the next day.

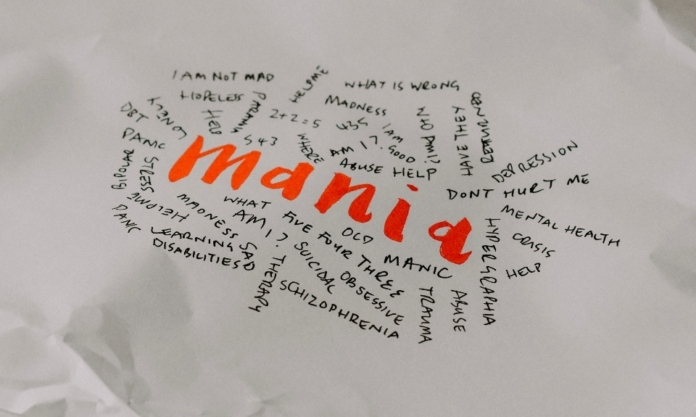

This sense of sliding between shades of reality is reflected in the book title. “Magical Thinking” is the belief that thinking, willing or wishing for something to happen may cause it to manifest. It has been hailed as a benefit to mental health when it produces a sense of calm, control and a positive mental attitude. It can also be symptomatic of obsessive compulsive disorder or schizophrenia.

As with all things in life, it does not lend itself to a simplistic, clear answer.

Lately, my mind has been congested. It began in lockdown, healthy summertime habits of daily constitutionals and food that is ripe for nurturing the body quickly gave way to the code yellow, self-isolation stint at home, the “oh well, maybe next time” cancellation of trips and the return to rigid routine.

The CDC defines grief as a “response to loss of life, as well as to drastic changes to daily routines and ways of life that usually bring us comfort and a feeling of stability”. This we know. And we’ve all had our fair share of the latter recently, and some of us of the former.

What grabbed my wily attention and dragged it face first into Didion’s book was her visceral laceration of a certain Dr. Volkan, and his technique of “regrief therapy, […] for the treatment of established and pathological mourners.” This technique allows the patient to review, redirect and ultimately “emotionally relive” the traumatic event. Whilst Didion assaults Volkan’s methods, ironically demonstrating the anger he predicts will appear if things are going well, she doesn’t dwell on the validity or value of the technique itself.

As September waxes and wanes, it may be worthy of consideration in the present context. None of us are lucky enough to skip through this life without wrenching an ankle, losing a limb, or saying goodbye for the last time to a life-mate. This is the nature of living.

Denmark has recently announced that COVID is done and dusted. The virus, being “under control” will no longer play a part in determining social and cultural norms. Ireland has rolled out similar plans to end all restrictions by October, 2021. Yet just recently, we have lived a resurgence that shows how quickly virus mutations and a loosening of restrictions can plunge us all back into a time warp of uncertainty.

The pros and cons of every territorial response to the pandemic are a moot point.

We all do the best we can. But regrief as a concept begins to take on a relevance that is undeniable. In each and every one of us, the past 1.5 years has not only dredged the bottom of the psyche, it has also created bespoke heartbreak for many.

Being locked in, being locked out, old loss and new; all of these krakens reframed and reinforced by the need to stay upbeat, the desire to keep on keeping on.

As year 27 dawns, I realise that I am no expert on grief, yet maybe I know a thing or two about regrief. This time 27 years ago, I stopped the kitchen clock, because its ticking reminded me of the clicking of bicycle spokes. I began my 1 year and 1 day oxtail-soup diet, because it was the only thing from a packet I could make that tasted like the past.

The shoes were thrown out, but just like right now, they were too small for me anyway.

Didion’s life mate did not return. The Year of Magical Thinking considers Emily Post’s 1922 book, “Etiquette in Society, in Business and in the Home”, and ponders the difference between then, almost 100 years ago, “a world where mourning was still recognised, allowed, and not hidden from view” and now, when an “ethical imperative to enjoy oneself” demands that grief be hidden from view, lest it taint the enjoyment of others.

The body is judicious in its use of fuel. The brain uses 20 percent of our daily allowance of resources. We rage, rage, rage against the uncertainty that is the daily fare, while another year dwindles into twilight.

“I look for resolution and find none”, writes Didion. Her grief, like that of those stranded in uncertainty, has no defined finish line. Perhaps all grief, in one way, is regrief; drawing up once more each time uncertainty, drastic change and lack of stability, manifest in daily life.

Magical thinking may derail the pathological reactions to life changing gear suddenly.

But as my grandma always said, better out than in. Regrieving is perhaps the kindest way to work through life events that are too hot to touch at the event horizon. And what’s more, it can help us to better understand what fuels our response to the new, unpredictably eccentric normal.

Regrief is an acknowledgment that life experience accumulates, and colours our perception of current happenings.

Congestion leads to build up. Build up leads to bursting. Emily Post recommends hot tea, broth or something that usually appeals to the taste. In other words, soul food, chicken soup and whatever gives you a warm fuzzy. Didion recommends it as “as prescriptive in […] treatment of grief as anything else I’ve read”.

September is a funny month for me, and this year, it’s a funny month for many of us here in The Southern Jing.

We look for resolution, and we find none. But I know this. Grief does not diminish. We grow around it, we grow bigger than it, we grow with it. It’s the process that is this tick-tock business of life. Congestion is only a resting stage. Stop all the clocks you need, drink hot tea and broth. Comfort and stability will reassert.